By the early 1970s, the state of Alaska was at a crossroads.

Changes from oil exploration to international fishing in waters off the coasts were bringing attention to a region that held vast swaths of territory largely unmapped and unstudied by federal planners. Central to this dynamic were Indigenous rights to ancestral homelands, and how best to resolve with new federally orchestrated efforts. What began as a lands protection effort, expanded in its undertaking to encompass a living record of cultures, subsistence lifeways, and landscapes unlike anywhere else in the nation.

The enactment of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) in 1972 (the year following its passage by Congress) was a government-led effort intended to resolve long-standing issues surrounding Indigenous land claims in Alaska, with a corollary goal to stimulate economic development throughout the state.

On the federal level, it was left to the National Parks Service (NPS) to create a new “Alaska Task Force” to facilitate efforts by the Department of the Interior to implement the national interest lands provision of ANCSA. In short, the group’s main goal was to help identify lands that should be withdrawn for inclusion in the National Parks. To facilitate decision-making, this Task Force conducted groundbreaking studies at both established parklands, and the newly withdrawn lands.

"Nowhere else in America are the landscapes and life communities so directly and obviously involved with the cultural heritage of the people"

Over the next six years, the Task Force identified almost 50 million acres of potential park land as candidates to be withdrawn for further study. New studies were also proposed to determine the extent of archeological, historical, and paleontological sites across the state; extending protection of some sites by federal and state antiquities acts; and involving Alaska Native communities in land use planning process.

This last point is one where the Task Force helped to raise the importance of subsistence use of lands across Alaska, and how this directly impacted these communities, and non-Natives who hunted and fished for means of either subsistence or pleasure. In May 1972, then-Secretary of the Interior, Rogers Morton, drove this point home for NPS planners:

“Nowhere else in America are the landscapes and life communities so directly and obviously involved with the cultural heritage of the people. In its growing involvement with cultural themes, the National Park Service would expect to work closely and successfully with the Alaska natives to ensure that new parks in Alaska are not only expressive of a national land ethic but also of the cultural heritage of these Alaskans.”

This question of subsistence was key to deciding how millions of acres of land would become integrated into 17 different national monument areas. In 1978, President Jimmy Carter made an executive action under the Antiquities Act which set aside 51 million acres of land for these new national monuments, with 80 percent falling under the jurisdiction of the NPS. They were places with notable Native names and included: Aniakchak; Bering Land Bridge; Cape Krusenstern; Gates of the Arctic; Kenai Fjords; Kobuk Valley; Lake Clark; Noatak; Wrangell-St. Elias; Yukon-Charley; and enlargements of Denali (formerly Mount McKinley), Glacier Bay, and Katmai.

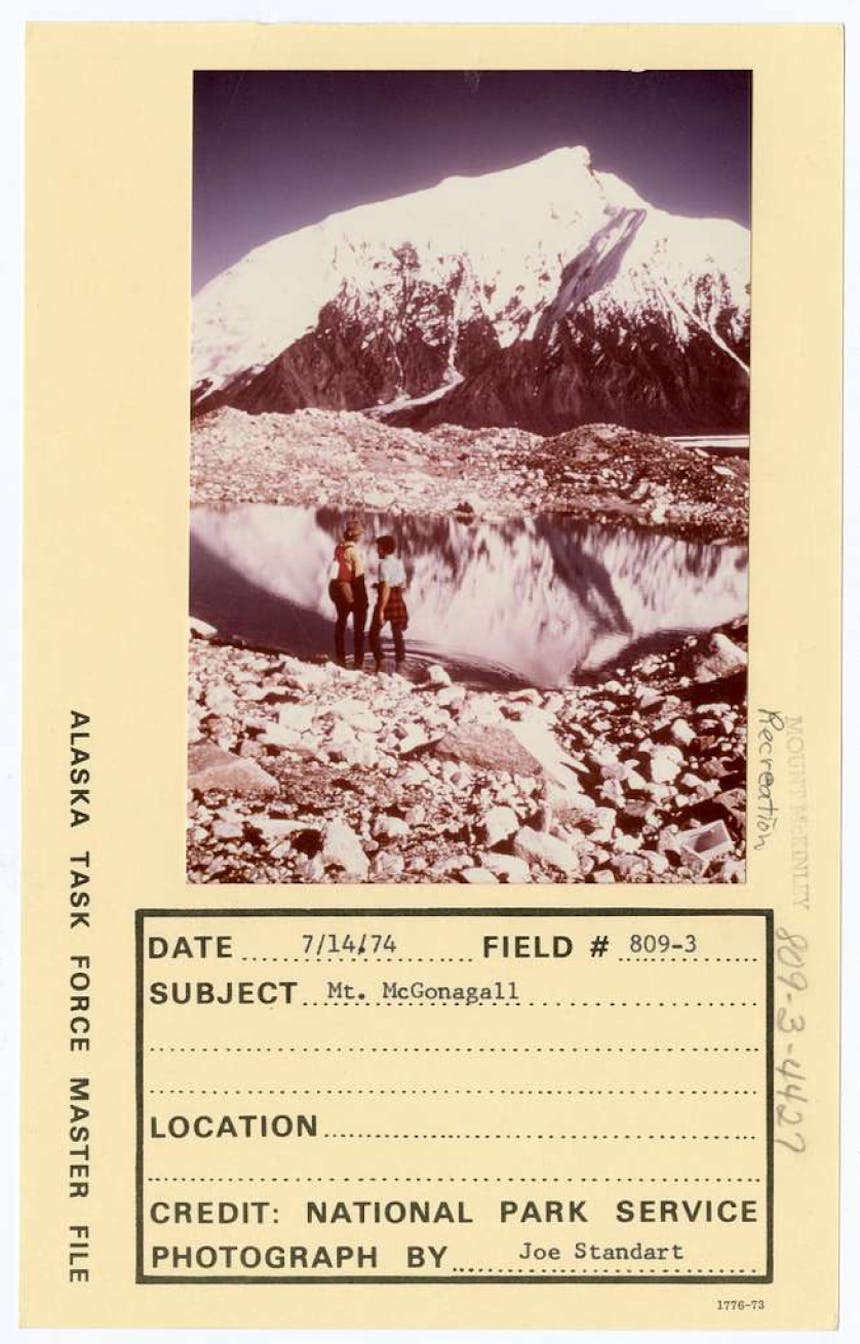

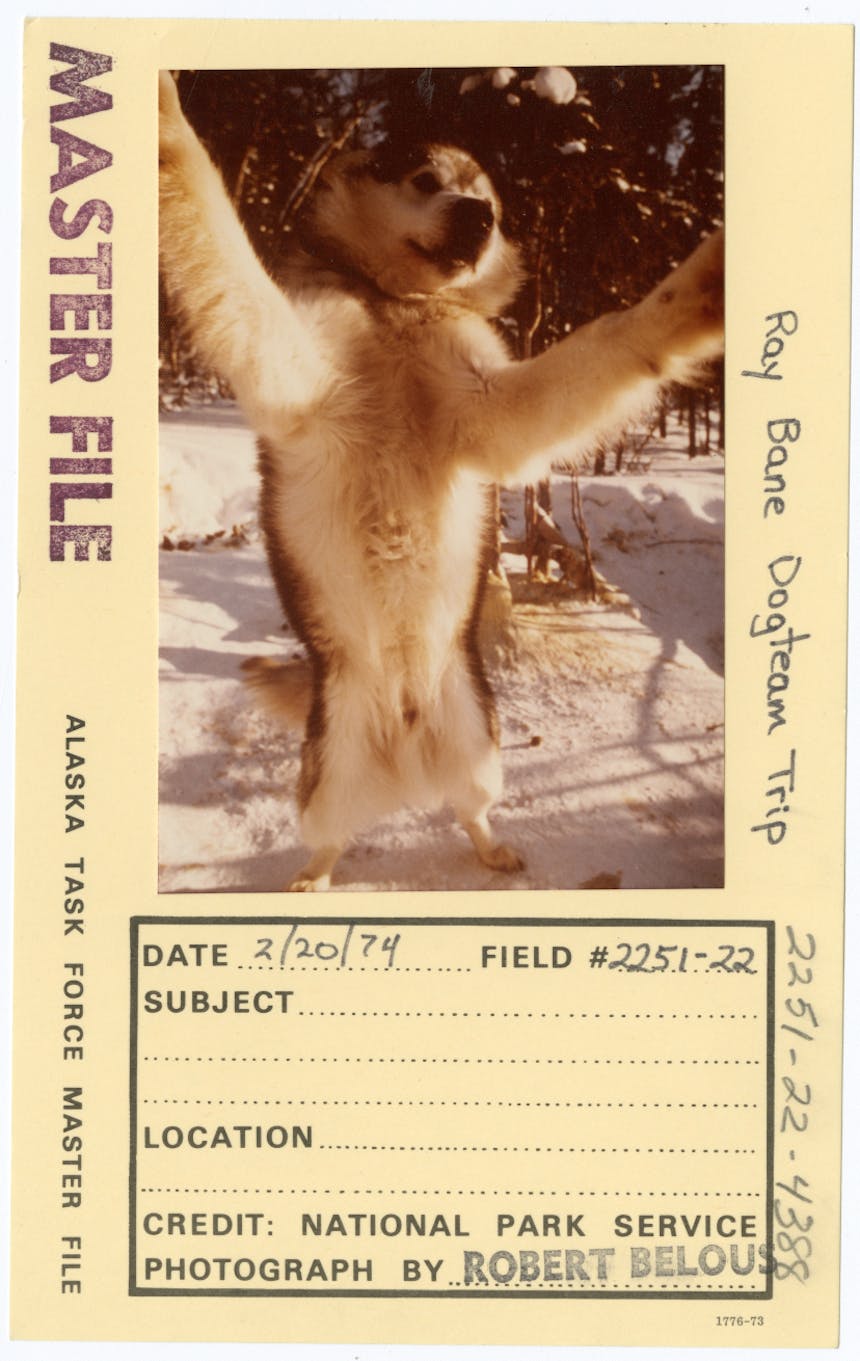

Much of the success of the Alaska Task Force can still be readily seen today, in its comprehensive and exhaustive photograph record of its review of Alaska, dating from 1962 to 1978. These photographs, collectively called the “Master File” by its creators, offer hundreds of views of the Alaska wilderness, from both aerial perspectives, and ground level. Nor are these limited to only landscape expanses of glaciers, rivers, mountains, prairies. They present accurate and unedited documentation of painted wood carvings, wildlife up close; native seal hunters curing skins, ice fishing, villages, burial sites & memorials, settler cabins and other structures; and remnants of those whose passage has become marked by relics from another era.

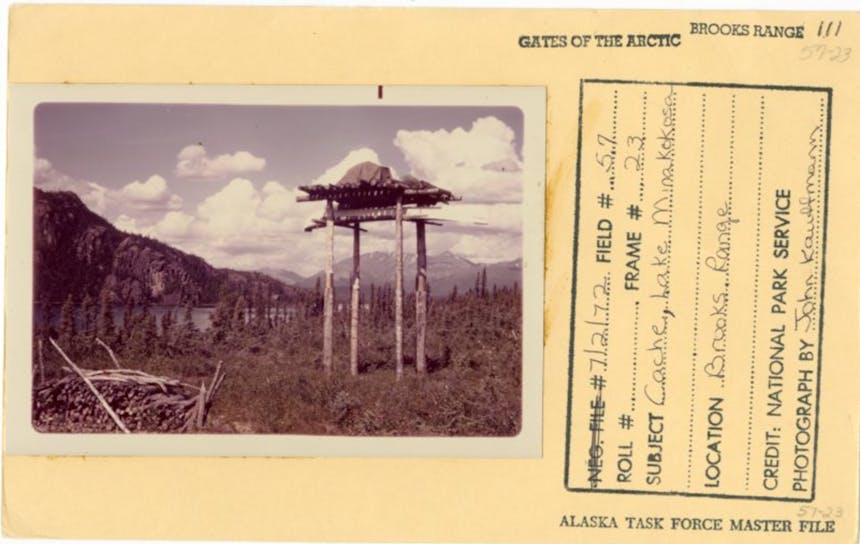

In viewing some of these Master File selections, descriptions of the subjects are limited to place names only, left open to interpretation. Such is the mystery behind the photo taken on July 10, 1972, that looks down on a manual cash register. Another image from the same year shows a handmade, raised wooden platform at Lake Minakokosa, identified only with the cryptic label “cache”. Other photos document subsistence activities that shed valuable light on the nature of these locations, and their importance to people – as seen in the photo: Fish wheel for catching salmon along the Yukon River between Circle and Fort Yukon.

Cache, Lake Minakoko

Today, the Department of the Interior has preserved the Task Force records and Master File photographs as part of its legacy to help preserve and protect the Alaska frontier as part of its National Parks System.