In Rick Myers’s garage sits a hand-built dingy—shiny with newness, waiting patiently for water. Adjacent, the oars that will propel it lie unfinished across two sawhorses. The illustrator holds a bench plane. With both hands, he runs the razor’s edge of the tool across the oar blade, and curly ribbons of red and yellow cedar fall in a fragrant pile around his feet.

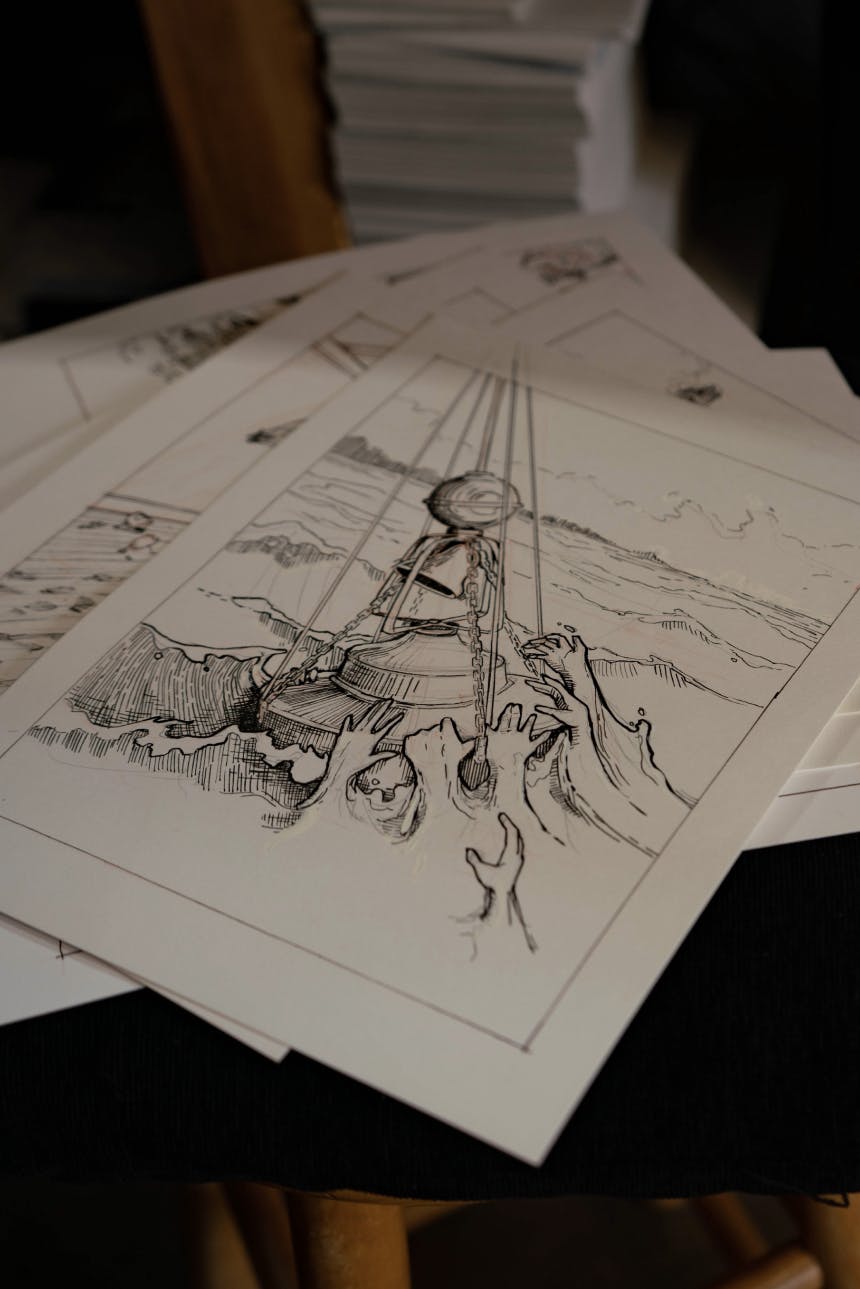

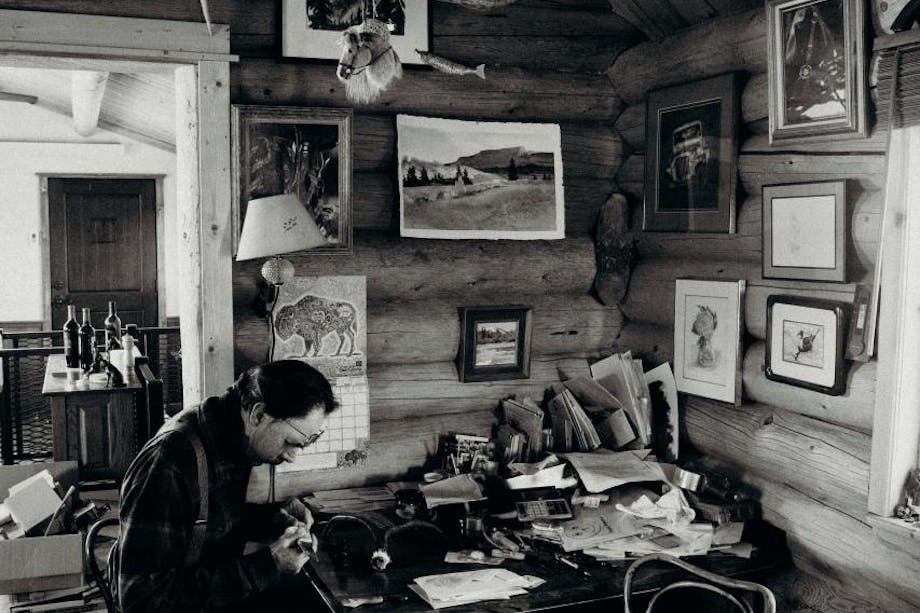

A cast-iron stove tucked in the corner struggles to maintain a number around fifty degrees. Left of this sits a petite wood easel with an unfinished painting. Left of that, a powerful computer runs an electronic drawing tablet and a large monitor. Along his workbench sit paper, some skulls, large dried mushrooms, and two small adjustable human figures. Five paintings are arranged next to the window. The subjects are ships, mountains, ice, and fire. Two bunches of dried chili peppers from New Mexico hang from the ceiling. A chair is available, but Rick does most of his work standing. A wizard staff sits in the corner—also hand-built.

“I’m a nerd. I play a lot of Dungeons and Dragons. It’s what got me drawing as a kid. I wanted a fantasy world where dragons existed.”

Several multi-sided dice from the game are tattooed into one forearm—rolling these decides a player’s fate. On his other arm is a kitchen knife with chanterelle mushrooms and onion—he has taken cooking classes from around the world. Laugh lines around his eyes and some almost invisible flecks of grey belie a youthful forty.

“I moved from Wisconsin in grade school to South Dakota through high school and some college. From there, I moved to Albuquerque.”

At some point in the mile-high desert, he felt inspired to buy “a sh**ty diamondback bike for fifty bucks” and cycle 3,000 miles back through the Midwest in a comma-shaped journey that finished up in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Back in Albuquerque, he worked at an organic grocery store, but not for long.

“I quit the job, walked over to the coffee shop, met a friend there, and then met my wife—because she was cute and had pink hair.”

Kristin, his wife, came with a guitar and a voice. We hear her sing from her album Tumbleweed, playing from his phone.

Together, they made their way to Evergreen College in Olympia, Washington, where Rick went to school for art. After graduation, they moved to Denver. Rick owned and operated three businesses—two in real estate and a board game store. Money and comfort came in exchange for a few breaks from a ringing phone.

“I wasn’t enjoying myself. I was comfortable. Comfort and happiness are not necessarily the same thing. I can think of a lot of uncomfortable moments when I was happy.”

It was time for a serious roll of the dice. Rick and Kristin quit their jobs and began a two-year sojourn. A drive to 40 national parks and across the Pacific Ocean to half a dozen countries to pristine beaches, ancient temples, and as high up as the Everest basecamp.

Two years later, the cash had been exchanged for all the happy discomfort that money could buy. They found themselves in Port Townsend, and Rick was drawn to boats.

“At first, I went to the desert…but when you think of the great adventure, you’ve got to sail to get there.”

Rick decided a place to start was the Northwest School of Wooden Boat Building. “The lead instructor always said something like ‘If you can draw it, you can build it.’ The lofting portion of wooden boat building helped me get back to the draftsman portion of doing artwork. Learning how to make lines again, learning my perspective.”

In Rick Myers's garage sits a hand-built dingy—shiny with newness, waiting patiently for water. Adjacent, the oars that will propel it lie unfinished across two sawhorses. The illustrator holds a bench plane. With both hands, he runs the razor’s edge of the tool across the oar blade, and curly ribbons of red and yellow cedar fall in a fragrant pile around his feet.

After school, he opened up a solo shop in his garage and worked briefly for the Northwest Maritime Center.

In January 2018, Rick’s father was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Eight weeks later, he was dead. Rick’s notepad was in his hand the first day of chemotherapy, and he sketched.

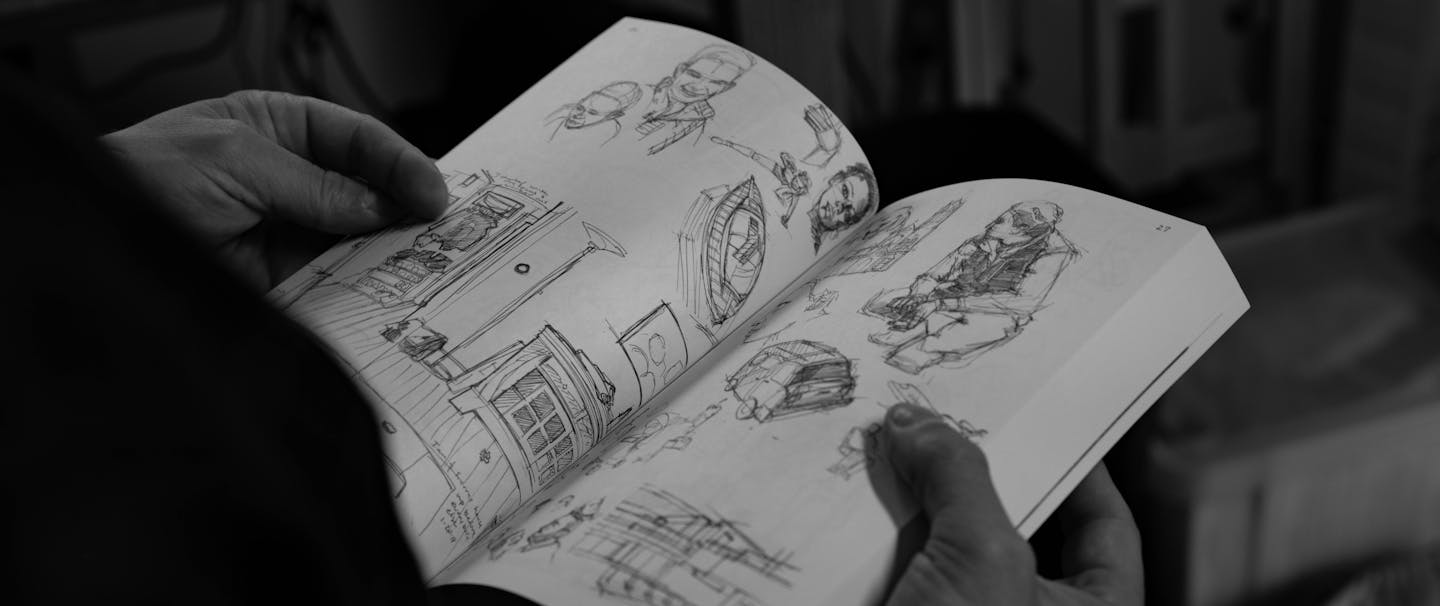

He picks up his book Practice and shows me the picture in the first few pages.

“When I came home, I didn’t want to do the work on boats anymore. I went to school for art originally. I’d done all this work to become an artist. Why not become an artist?”

The rest of his book, about an inch thick, is filled with boats, nature, faces, creatures real and imagined, and scenes from around Port Townsend.

“There is so much whimsy, fantasy, and magic that’s taken out of the world right now—and ways to put it back in—if you can do something to put it back in,” he ruminates.

The book has 1,200 scans of artwork done in the year and a half since his father died. He’s at the beginning of his career but has traveled far.

“Put in the hours. You draw your circle. Your circle is okay. Now draw a hundred, draw a thousand. Draw every day—at least once. Draw and draw and draw some more—I’ve got a vision in my head of what I want.”