The month of July 1897 was an exciting time to be living on the West Coast. Steamships with names like Excelsior and Portland were docking in the ports of San Francisco and Seattle, respectively, loaded down with tons of gold mined from the Klondike region of the Yukon territory of Canada. Alaska was the gateway by which anyone with a desire to strike it rich could make the journey northward and, if well prepared and lucky, eventually return to civilization a millionaire.

In the first 99 days of 1898, a grand total of 107 ships set out for the Klondike with fortune seekers from Seattle. During the height of the Klondike Gold Rush between 1897 to 1900, an estimated 100,000 people made the attempt to get to the Klondike via Alaska: an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 finally reached their destination.

The majority of these would-be prospectors – called “stampeders” (in their rush to reach the Klondike) or “sourdoughs” (the latter named for the flour-like biscuits that were a miner’s food staple) – embarked north from Seattle aboard one of a fleet of steamships that made regular runs. Others left from West Coast ports that saw steamer service calls, such as Tacoma, Vancouver, Portland, and San Francisco.

What was travel on a steamship like in those initial summer days of the 1897 gold rush?

Passage on a steamship was the first leg of the journey for many, beginning in one of the West Coast ports and ending in St. Michael, Dyea, or another Alaskan coastal port. Next, it was a matter of getting upstream to Dawson City, via a shallow-bottom steamer (or in the case of Jack London, with hired Indian guides and their canoes). The ocean voyage was a matter of days or weeks, depending on the weather. Once arrived, many found that the subarctic weather had already set in, making passage up the Yukon river impossible once it turned to ice. More than 2,000 found themselves wintering over the 1,700-mile stretch between Norton Sound and Dawson City, waiting for the spring thaw before they could move on (or back to Seattle).

Did steamships allow for passenger cargo? Many of the prospectors did outfit and provision themselves in Seattle or the other ports of call before making the passage north. The Canadian government required each person to bring enough food and equipment to last a year. The cities provided any number of services, ranging from clothing outfitters and mercantile goods to hotels, gambling parlors, brothels to pass the time or coin while waiting for the next outbound ship. Along with provisions and mining equipment by the score, animals such as horses, dogs, and mules were shipped out in great quantities, many destined to die of abuse or starvation in the service of their northern masters.

Besides the maritime routes, another overland route to the Klondike gold fields, via Edmonton Trail through Alberta, was advertised as the “back door to the Yukon.” How many actually reached the gold fields, via this overland route?

The Edmonton Board of Trade claimed that the Klondike could be reached using horses in just 90 days. What they failed to mention was that the 2,000-mile route was through Canadian wilderness of forests, canyons, prairie, mountains and rivers, with nary a “trail” to speak of, let alone a road. One of the many poor souls to perish taking the route wrote on a scrap of paper “Hell can’t be worse than this trail. I’ll chance it,” before pointing the barrel of a gun to his head. Of an estimated 2,000 men and women who took the Trail option, fewer than a hundred made it alive to Dawson and none struck gold.

The museums of Seattle today offer a few tantalizing clues as to the identities of some of the prospectors who journeyed north. In its North America gallery, the National Nordic Museum mentions Andrew Nylund, a Finnish immigrant to the United States who ventured north after the major gold rush to Alaska, arriving in 1913 to pan for gold in the Klondike. The iron pan he used to sift gold flake and nuggets has hand-punched holes in the bottom, the edges rusted from countless hours of water draining out the bottom to leave rich findings. Next to the pan is a vial of gold dust recovered from Nylund’s efforts: part of the success he achieved, as he also met his wife, Ida Nylund, who also came to Alaska from Finland at age 16.

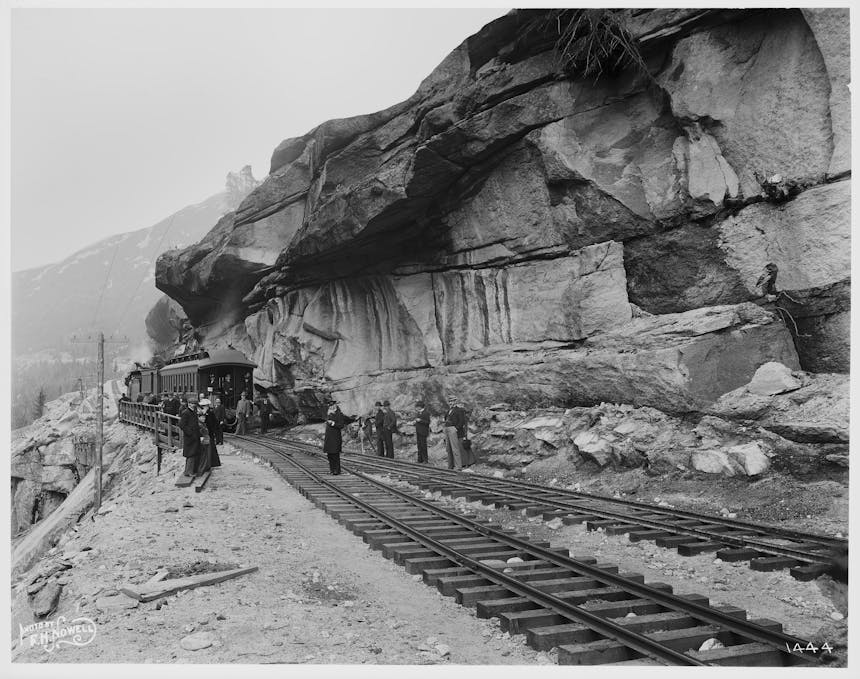

Another excellent source of Klondike Gold Rush history comes from the Museum of History and Industry’s (MOHAI) photographic archive. Photographers from the era offer views of scenes such as the Alaska Steamship Company at Piers 1 and 2, Seattle, circa 1898; views of the snowbound Chilkoot Pass and its treacherous route made by foot and pack animal through the mountains to the gold fields; another view showing the packed freight yard at Dyea in 1898 – with its narrow harbor, ships had to anchor far offshore and have their cargos ferried in for delivery.

The history of the individual steamships is as varied as the stories of the prospectors who ventured north in search of gold. An excellent source of detail about many of these ships is Gordon R. Newell’s edited book, TheH.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Some of these ships became well known as the heralds of good fortune; others suffered terrible fates either en route or returning from the Klondike, or later in their careers once the gold rush had ended. Companies such as the North American Transportation and Trading Company, Northwestern Commercial Co., Alaska Exploration Co., and the Pacific Coast Steamship Company looked to capitalize on a seemingly endless flow of new passengers determined to head north (or south –returning either bust, having spent all their funds, or, for a happy few, successful). The steamship companies competed with one another to offer the fastest ships able to reach Cape Nome, Cape York, and St. Michael, all launching points for anyone headed into the Alaska interior. A sampling of these include:

SS Portland

Built in Bath, Maine, in 1885 and christened Haytian Republic, this ship started its career as a notorious opium runner and Chinese smuggler. It later started the gold rush to Alaska in 1897 with its delivery of $700,000 of gold to Seattle on July 17, 1897.

SS Hassler

The Pacific & Alaska Transportation Co. was formed by parties who acquired the iron-hulled steamship Hassler, after it was condemned and sold by the U S Coast & Geodetic Survey service. This craft was renamed Clara Nevada (in honor of a well-known Western actress of that period) and placed in service between Seattle, Skagway, and Dyea with a capacity of 100 first-class passengers, 100 steerage, and 300 tons of freight. This enterprise was short-lived, as she completed only one round trip before providing one of the worst of the gold rush marine disasters, when she struck an uncharted rock at night near Eldred Rock and sank with no survivors.

SS Morgan City

One of the more successful of the Alaska sourdoughs, Joseph Ladue, the founder of Klondike City, invested some of his wealth in the steel steamship Morgan City, which was brought around from New York by Captain John G. Dillon. Ladue’s Yukon Transportation Co. (the Gold Pick Line) was short-lived, the Morgan City being one of the early Alaska steamers to be selected for the lucrative Army transport service to Manila from the Pacific Coast in 1898.

SS Excelsior

This steamship brought in $500,000 of gold from the Klondike to San Francisco’s harbor on July 14, 1897.

SS City of Tacoma

Built as the Batavia in the British Isles in the 1880s, this steamship was sold to the Northern Pacific Company and placed in the silk trade, running from the Orient to Tacoma. It serviced passengers during the Alaska gold rush and after 1890 was sold to the Russian government.

SS Alki

The long career of the pioneer Alaska steamer Alki (or, Al-Ki), one of the most famous of the gold rush treasure ships while under Pacific Coast Steamship Co. ownership, ended its career in 1917.

SS Nome City

The well-known steamer Nome City, prominent in gold rush trade to Alaska and later in service between Portland and San Francisco, was purchased from George D. Gray by Charles Nelson & Co. and added to that firm’s growing fleet of lumber carriers in February 1912.

SS Discovery

The little steamer Discovery, which had been flirting with the perils of the Alaska route since gold rush days, also met disaster in 1903, with the loss of all hands aboard. The Discovery had been launched at Port Townsend in 1889 as a 90 -foot steam tug for Capt. Thomas Grant, who operated her successfully in that trade until 1898, when she was placed in passenger and freight service to southeastern Alaska, still under Capt. Grant’s command. Early in April of that year, she had barely escaped disaster on her down trip from Skagway, stranding on a reef near Berners Bay.

The passengers were taken ashore and in the morning it was seen that the beach in the vicinity was strewn with wreckage from the ill-fated Clara Nevada. At high tide, the steamer was refloated and proceeded on her way, only to meet a fierce blizzard in Queen Charlotte Sound, at the height of which a gasket blew out of her boiler, leaving her powerless. Capt. Grant personally directed repairs, which took some two hours, while passengers and crew formed bucket brigades to bail out the leaking vessel by hand. She also survived this ordeal, only to sink at the Pacific Coast Company bunkers in Seattle a few days later.

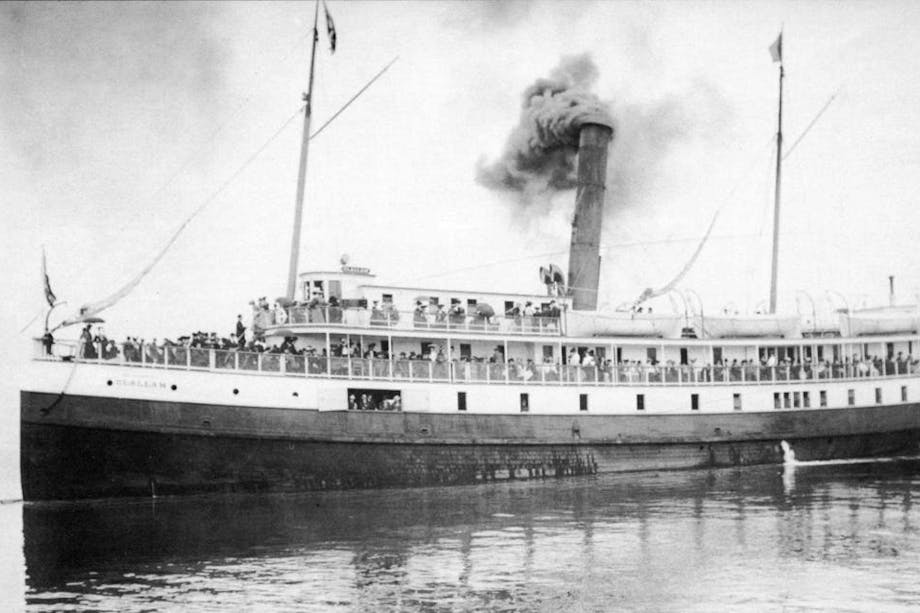

SS Leelanaw

The steamship Leelanaw, brought to the Pacific Coast during gold rush days by the Alaska Exploration Co., and later well known in the bulk cargo trade, was torpedoed and sunk off the north coast of Scotland on July 25, 1915 while carrying flax from Russia for Great Britain.

SS City of Seattle

The steamship City of Seattle, known as the old “Alaska Lightning Express,” was sold by the Pacific Steamship Co. to C. L. Dimon of Jacksonville, Florida, for the Miami Steamship Co. Also called the “Alaska Flyer” during the gold rush days, the ship was sold on the East Coast by the Miami Steamship Co. and scrapped at Philadelphia, where she had been built in 1890.

SS Jessie

One of the mysteries of the gold rush was the disappearance of the expedition aboard the little steamer Jessieand the barge Minerva. A party of fourteen, the majority men from Kentucky and Tennessee, departed from Seattle on May 31, 1898, bound for a combined gold-seeking and trading expedition up the Kuskokwim River. They made the voyage to the mouth of the river aboard the steam schooner Lakme, which towed the barge. Admiral carrying the expeditions small steamer and barge. Passing through the Aleutian Islands, a Moravian missionary, Rev. R. Webber, his wife and two children joined the party. The Lakme reached Kuskokwim Bay on June 27 and discharged the passengers, steamer and barge. Next morning the Jessie took the barge in tow and the party started up the river. There seems no doubt that the two vessels very shortly swamped in the turbulent waters at the mouth of the river, but the subsequent fate of the 18 passengers remains unknown to this day.

SS Margaret/Charles H. Hamilton

Although construction began and was subsequently rushed to completion on a large fleet of river steamers in Alaska, many of them shipped north “knocked down” and assembled there, most of these did not get into service until the following year in 1898. The Margaret of the Alaska Commercial Co., 520 tons with dimensions of 140 x 33 x 7 ft, with the 250 horsepower engines from the old Arctic, and the Charles H. Hamilton of the North American Transportation & Trading Co., 595 tons, 190 x 38 x 5.5 and of similar power, were among the stern-wheel steamers to go into commission at St. Michael that year. Although the Hamilton was somewhat underpowered and unwieldy, she was of great capacity, and the Margaret although lighter and handier, was also a good carrier, and both proceeded to reap the profitable harvest of early gold rush days on the Yukon.

The steamship and the prospector have an intertwined history, with respect to the gold found in Alaska and the Yukon. Some found notoriety and fame, while most endured the cold environment with little to show for it at the end. The stories of riches continue to enthrall people to this day.