Peter Hall and his father set out on a Yukon Moose hunt, by way of canoe, into the remote reaches of the Alaskan wilderness. The time they shared on the river reminded them both that the glory of adventure is found far beyond the kill.

At one in the morning the aurora fills the sky. The remaining hour drive to Eagle, Alaska, puts us so far north that the bands of aurora ripple on a sharp curve around the pole. The bathroom break takes twenty minutes as my dad and I gaze at the purple and green piano-key ribbons. The overland portion of our journey will end in Eagle, but it will not be tonight, or tomorrow night.

My dad and I prefer to do things on our own. I do not know if it is the freedom that comes with self-reliance or foolish pride – those two are hard to tell apart sometimes. The seasonal car shuttle business calls it quits by the end of September, so in order to float 158 miles of river, I drop our gear in Eagle, drive twelve hours to Circle, Alaska, bum a ride back to Fairbanks, and hope that the flight to Eagle flies the next day. When it cancels, a friend that I now owe too much drives me to Eagle on his way back to the lower forty-eight. With the boats loaded, the rigorous logistics do not get another thought as the Yukon River’s current grabs my canoe for the first time.

I grew up in Montana doing all things outdoors in legendary wild places, but to be sitting in a canoe on the Yukon is like an out-of-body experience. In the center of the Bob Marshall Wilderness, I almost talk myself into the feeling of wilderness. Of course, the Bob Marshall is a wild place, but at Big Prairie, I can walk to a traveled road in almost any direction in a summer day. That is no longer an option just a few hours down the Yukon.

The river becomes terrifying if you think about it too much. Between Eagle and Circle, depending on flows, the river current averages five to eight miles per hour (that is blazing fast). When we shove off, there is 100,000 cubic feet of water passing the town of Eagle every second. Because of its glacial source in British Columbia, the green and chalky water obscures your feet at shin depth. Since the river is low, the dry side-channels reveal the river’s wild nature with swales, holes, and gravel bars that can move up and down twenty feet. My canoe sounds like radio static as it amplifies the sound of tons of gravel washing along the twists and turns of the river bottom. Now and then, like the sickening crack of heads hitting each other, the sound of two boulders knocking in the murky depths pops through the hull.

The first night, we camp about thirty miles down the river from Eagle. Tomorrow we will be on public land and 120 miles of hunting from canoes will begin. The only flat spot that is not thick with alder is a fresh moose bed. Sitting in camp at dusk, with the musk of moose piss palpable, a Canis lupus choral score rises and falls over the muskeg.

My own dear Canis lupus familiaris has a habit of putting her nose in my ear while I nap, then start sniffing wildly – probably to watch me jump out of my skin. Tonight, a critter with nares many times larger than my dog’s pulls this prank. I do not jump out of my skin, though – this is serious. I lie there breathing lightly, my eyes slightly wide. I listen for its next move, trying to decide if the time is right to create a bluffing conniption. When the beast wanders off, normal breathing returns; I start to calm down, and go back to sleep. This is my first experience of a bear sniffing around the tent. As a thirteen-year-old in the Bob Marshall, my dad experienced this. When I heard the story as a boy, I asked, “What did you do?” He responded, “Nothing. Nothing you can do.” Apparently, the moral of that story was not lost on me. When I tell him about it in the morning, he says, “Huh, didn’t hear it.”

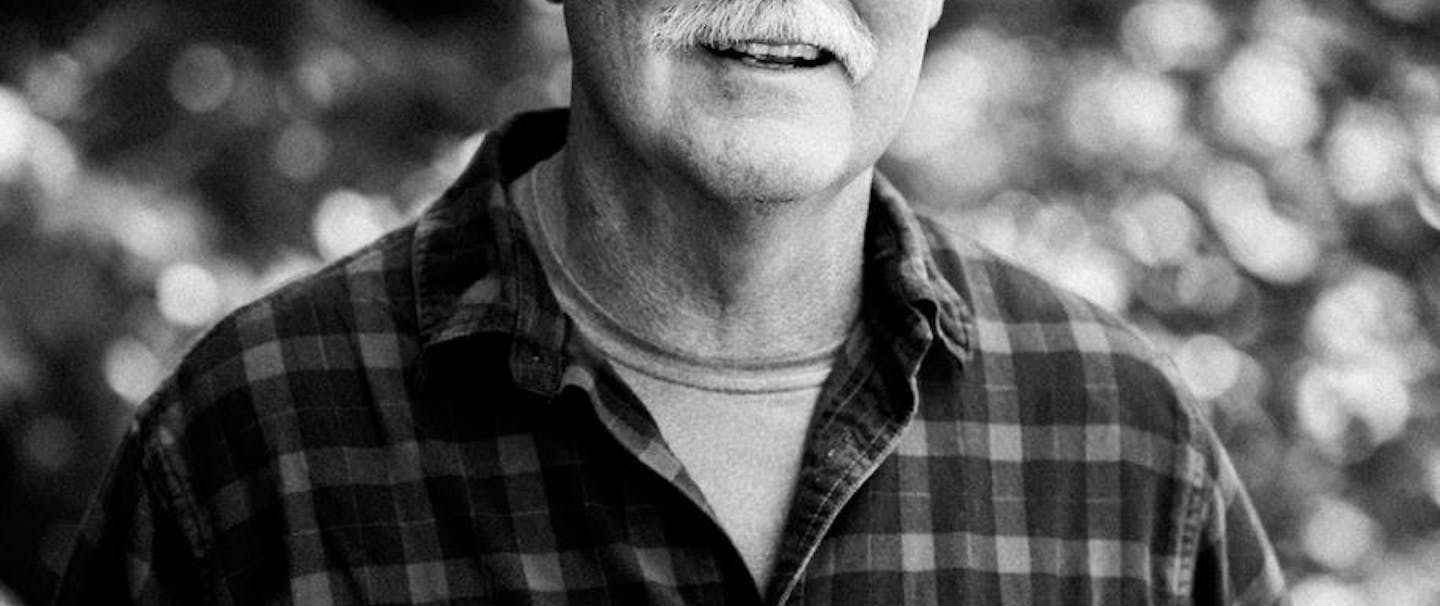

My old man is six foot two and built like a guy who has spent his life working in the mountains. He possesses a nearly unmatched stoicism, especially in the woods. But he has a healthy sense of humor that helps when adventures go awry. His demeanor made coming of age in the woods very grueling and equally rewarding.

As we hunt, we paddle for hours at a time. We walk miles of side channels and sit in our boats through every type of weather. Lunch is pilot bread, Cheddar cheese, and pickled pink salmon next to a driftwood fire. Then we get back on the river or hop-scotch the muskeg’s tussocks.

We see one bull moose in the first few days. It is not a legal bull. Not even close. In this game-management unit, a non-resident hunter is only allowed to kill a moose that has four drop tines or an antler spread of fifty inches. The drop-tine method is a sure way to determine a bull’s legality. But watch for a point that can grow in the space between the drop tines and the paddle. Without looking carefully, it is easy to count that point with the drop tines. The fifty-inch spread can be accurately judged if you can get a view of the moose’s head straight on. Looking straight forward, the overall distance from eyeball to eyeball on an adult moose is ten inches. So, imagine stacking that distance twice on either side of its head, and if the antlers are wider than your imaginary head stack, you have a legal bull. This first bull misses on both accounts.

Luckily, our hunting is not entirely fruitless. Tonight, we sit around the tent stove scarfing down red squirrel stew – the meat collected during bathroom breaks along the river. Onions and tubers (and beer) come along easily on river trips. Eating camp-meat and fresh veggie stew (with a stout) is a soul-quenching affair after pulling on a paddle all day in the wet cold. The one day I do not carry my camp-meat-scrapping .22 handgun, a spruce grouse flushes into a tree beside me while paddling backwaters. My dad, behind me, cannot see it, so I ask him to hand me his .22 handgun, wisely loaded with subsonic pellets. He hands me the gun as he tries to spot the bird. I take the gun, level the sights a little high, and squeeze. Hardly more sound than the hammer hitting the firing pin reports, then the tree erupts with the flailing of a head-shot bird. As it thrashes its way down the tree, I hear my dad say, “I’ll be darned.” This is the best compliment I have received while hunting.

Between the evening of squirrel stew and tonight’s campfire-grilled spruce grouse, we set up a spike camp for the last days of the moose season. Our camp is on a creek next to a rocky bluff overlooking a vast swampy flat. We hoof it up the bluff and glass the flat. We also paddle the creeks to learn their layout so that if we spot a bull we can be there quickly and silently by canoe. On the last day of the season we spot a potentially legal bull. He is browsing a marsh that we could get to in fifteen minutes. After watching him for a while, I finally get a head-on view and judge him to be about forty inches. My dad agrees. At this point I figure we will have empty boats the rest of the way.

As the sun sets on the moose season, I am too distracted by the scene around me to worry about light boats. The harshness and beauty of more than a week on the Yukon hangs in one place for a few moments. The clouds scuttle by close enough to touch; the sun filters through at a low angle and sets the yellow birch and orange alder aflame on the braided islands and riverbank. The contrasting bright foliage and turquoise river, and the black spruce fading to green muskeg, change kaleidoscopically under the passing clouds. Appropriately, there is never enough sun to drive away the pervasive shroud of cold mist. I am overcome by a squall of unique joy. This is what Annie Dillard called “seeing the tree with the lights in it.” And I too live for it.

It is a lie to say there is nothing I would change about this trip. The change I would make is probably obvious. But I learned at an early age from my own adventures and the tutelage of my stoic father that backcountry trips are often total failures. They are always uncomfortable. And frequently they are more glorious than you can imagine. Usually, they are all three.

Story and photos by Peter Hall