Nothing feels small on the Skagit River. It emerges from the Cascade Mountains, the ridgelines rising suddenly and severely, compressing the landscape and framing the view with their immense, sharp mass. For much of its length, the river is wide enough that three or four drift boats could easily pass side by side with plenty of room to spare. Anglers standing in its flow could never dream of reaching the far bank with a cast. If that angler is fly fishing, then they are likely to be using a two-hand rod to throw a Skagit head, a short specialty fly line developed on its namesake river a generation earlier to deliver big flies and sinking lines to winter steelhead-holding water.

The Skagit is the largest watershed draining into Puget Sound. Its headwaters form on the Alison Pass of southern British Columbia and the river enters 162 miles later, immediately north of Camano Island, after draining a basin encompassing nearly 3,140 square miles. Two immense volcanos, Mount Baker and Glacier Peak, tower over the basin. In its final distance, its huge channel braids and forks, forming Fir Island and miles of tidal estuary in the process.

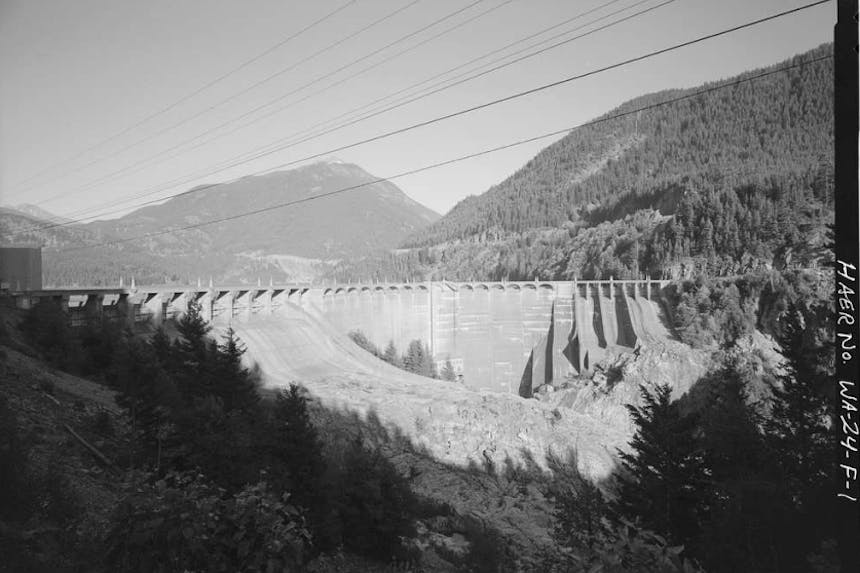

The river flows hard and fast in its upper reaches as it plummets down from the Canadian Cascades. Three primary tributaries – Snass Creek, the Sumallo River and the Klesilkwa River – join before it reaches Washington. Immediately south of the border, in the remote northeastern corner of Whatcom County, the Skagit is impounded by a series of three large dams comprising the Skagit River Hydroelectric Project. A fourth dam was planned but never built. The dams – Ross, Diablo and Gorge – were built between 1921 and 1940. Additional height was added to the Ross Dam in 1953. The Gorge Dam, the first of the three constructed, was replaced in 1961. All three dams are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Together, they provide approximately 20 percent of Seattle’s electricity. The reservoir of the Gorge Dam, the lowest of the three, inundates a steep canyon. Beneath the impounded water is a series of waterfalls and rapids thought to be the historical barrier to salmon and steelhead migration.

Below the Skagit Gorge, the river begins to slow as it leaves the mountain gradient. It is soon joined by its largest tributaries – the Sauk, Baker and Cascade Rivers – and meanders across a wide glacial valley containing some of the richest farmland in the Pacific Northwest before finally reaching Puget Sound. That black soil was formed over millions of years as alluvium composed of glacial silt was deposited by the river and fed by vast swathes of forest, wetlands and the marine nutrients brought inland by the bodies of countless generations of salmon.

Those salmon also sustained the Skagit, Swinomish and Sauk-Suiattle Tribes, the Salish people who, according to archeological records, have lived in the watershed for at least 8,000 years. Much later, when Europeans arrived and settled in the valley, they named the river for the Skagit Tribe and began to establish themselves on the land. They also depended upon the river’s salmon, and fished intensely. They cleared wetlands to make farms and clear-cut the hillsides for the lumber that built cities across the Pacific Northwest. Later, with steel and concrete, they built the dams to harness the river’s power for electricity.

More than anything else, the Skagit is an expansive fish nursery. The habitat diversity contained within the watershed supports a comprehensive list of native Pacific Rim species. Among others, it is home to all five species of Pacific salmon, both summer and winter steelhead, resident rainbow trout, coastal cutthroat, bull trout, and sturgeon. Historically, these fish returned to the river in astounding numbers. Estimates based on biological research puts those counts in the hundreds of thousands annually.

But over the course of the 20th century, as population grew, habitat was degraded and fish harvest accelerated, the Skagit’s ability to produce and rear salmon and steelhead diminished.

“The mighty Skagit is fighting to hang on against the ravages of the past and the changing climate of the future. But wade in its waters today, and its power and resilience feels palpable.”

When it was included in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System in 1978, the Skagit River’s designation was the first of its kind to include crucial tributaries. This was a holistic effort to protect the functioning of a connected river system. The Sauk, Suiattle and Cascade Rivers were protected in the original designation, and Illabot Creek was added in 2014. The Baker River couldn’t be included because of the pair of large dams already constructed there. Sections of the Skagit reserved for a proposed fourth mainstem dam and a nuclear power plant were also excluded from Wild and Scenic designation, though neither was eventually built.

The vast amount of habitat on the Skagit is the lifeblood of the system and the source of cautious hope for the future. Even in a diminished state, the Skagit still produces most of the Chinook salmon in Puget Sound, a crucial food source for endangered orcas. Chum and pink salmon numbers have varied in recent years. Sometimes they have filled the river again, and at other times returns have been feeble and deeply concerning. Baker River sockeye have increased again due to efforts by biologists to get them above the dams to spawn. Winter steelhead, after reaching such low numbers that the Endangered Species Act forced the state to close the fishery, have showed population increases and allowed for catch-and-release spring seasons again in 2018 and 2019. This recovery is reason for celebration, but it remains tentative and fragile. As I write this essay, Washington announced that low projected numbers of returning steelhead meant that this season would close again in 2020.

The mighty Skagit is fighting to hang on against the ravages of the past and the changing climate of the future. But wade in its waters today, and its power and resilience feels palpable. Scientists point to it as one of our best remaining salmon and steelhead strongholds. They point to the habitat that remains protected and intact, improved flow regimes from the dams and the immense amount of habitat that could be restored. Side channels, creeks and important wetlands and sloughs could be reconnected. Runoff could be managed for better water quality, and riparian zones are being replanted. All of this work supports ecosystem function and provides the habitat steelhead and salmon need to spawn and grow.

Throughout the watershed, many advocates, tribes and state and federal agencies, including the Nature Conservancy, the Skagit River System Cooperative and the Wild Steelhead Coalition, among others, are intensely focused on the Skagit’s potential to heal. There is much recovery work remaining. But for those of us who dream of a river system once again filled with bright chrome fish returning to cold water after years spent roaming and feeding throughout the North Pacific, there is no choice but to do whatever is required for the Skagit to thrive long into the future.

Image courtesy of Jason Hummel