The First Black National Park Superintendent

Born in 1864 to former slaves in May’s Lick, Kentucky, Charles Young might understandably have envisaged a bleak future. But his academic appetite drove him forward; his aptitude for foreign languages and music helped him graduate with honors in his high school class and led him to the military academy at West Point. There, Young endured racial taunts and ostracism from his fellow cadets to become just the third African American to graduate from the academy.

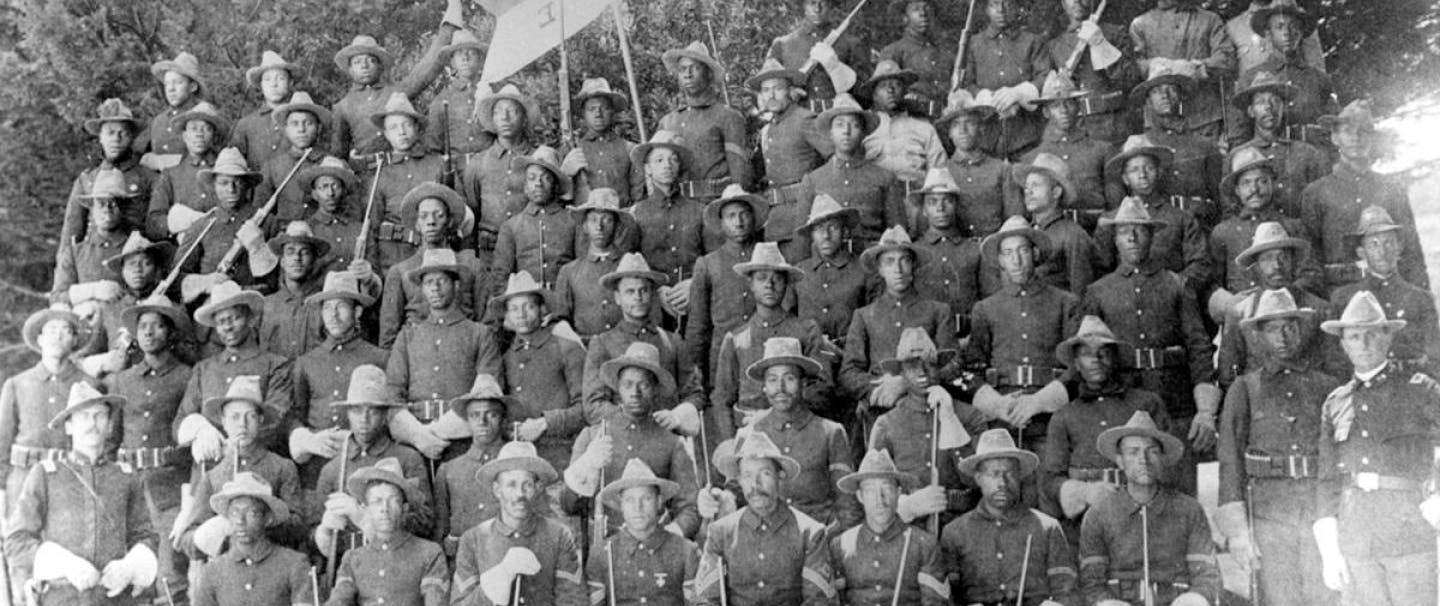

Young’s ties to the National Park Service were relatively short—just one year—but he left a mark that remains today. While stationed at the Presidio in San Francisco in 1903 as captain overseeing a detachment of Blacks known as the “Buffalo Soldiers,” he was ordered to Sequoia National Park, which had become the country’s second national park in 1890. After a 16-day ride to the park, Young put his troops to work building trails and roads, one that reached Moro Rock and another that entered the Giant Forest.

Though he spent just one year in Sequoia, Young left with the distinction of being the first Black park superintendent in the National Park System, and one who saw the construction of roadways that are mirrored today by the park’s roads. Young left the park in 1904 with a deep appreciation for the place.

“A journey through this park and the Sierra Forest Reserve to the Mount Whitney country will convince even the least thoughtful man of the needfulness of preserving these mountains just as they are, with their clothing of trees, shrubs, rocks, and vines, and of their importance to the valleys below as reservoirs for storage of water for agricultural and domestic purposes. In this, then, lies the necessity of forest preservation,” he wrote.

Lake Clark National Park & Preserve

In the end, Dick Proenneke’s desires were simple. Restless growing up in Iowa, he dropped out of high school and headed west on his motorcycle, an itinerant soul. The day after Pearl Harbor was bombed during World War II, he enlisted in the Navy. But that endeavor was derailed by rheumatic fever, which left him in the hospital for six months, a stint that saw the war end before he was healthy.

Odd jobs—a ranch hand, heavy equipment operator, diesel mechanic, and commercial fisherman—led Proenneke to Alaska. There, having read Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, and Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac, Proenneke began to find clarity. He sought quiet, wilderness surroundings and an uncluttered life. He found them all in 1968 in a remote slice of The Last Frontier, where he cleared a patch of land, felled spruce trees, and built a log cabin that gave him shelter and peace for three decades. Ironically, it also brought him national fame through a 30-minute National Park Service video, One Man’s Alaska, as his homestead became part of Lake Clark National Park and Preserve in 1978.

“I have found that some of the simplest things have given me the most pleasure,” Proenneke wrote in one of his daily journals. “They didn’t cost me a lot of money either. They just worked on my senses. Did you ever pick very large blueberries after a summer rain, walk through a grove of cottonwoods, open like a park, and see the blue sky beyond the shimmering gold of the leaves? Pull-on dry woolen socks after you’ve peeled off the wet ones? Come in out of the subzero and shiver yourself warm in front of a wood fire? The world is full of such things.”

The First Permanent Female National Park Ranger

Perhaps it’s only fitting that Yellowstone, the world’s first national park, should also hold the distinction of employing the first permanent female ranger in the National Park Service. But then, Marguerite Lindsley brought a unique pedigree to the job.

She had been born in the park in 1901, the daughter of Chester Lindsley, who served as acting Yellowstone superintendent when the U.S. Army transferred oversight of the park to the fledgling National Park Service. Initially homeschooled by her mother, Marguerite attended Montana State University and then received a degree in bacteriology from the University of Pennsylvania.

But her childhood days in Yellowstone prompted her to leave a job in a Philadelphia laboratory and head back to the park, on a Harley motorcycle with a girlfriend riding in its sidecar. Back in Yellowstone, where she had held a seasonal position as a naturalist under Superintendent Horace Albright in 1921, Lindsley in 1925 became the Park Service’s first permanent female ranger.

During her career as a permanent ranger, Lindsley helped to normalize women’s positions in the NPS. One example was designing her own uniform because the NPS did not have an official ranger uniform for women. An adapted version of this uniform was imitated by other female rangers and would eventually become standard.

The Prototypical Park Ranger

There’s a spot, not too far into Yellowstone National Park’s backcountry, where the idea of park rangers came to life. Today, all that remains are some chimney stones and subtle signs of a homestead. This was Harry Yount’s place for a year, beginning in the fall of 1880. That’s when the Civil War veteran was hired to thwart poachers.

With his sweeping beard and bushy mustache, and dressed in buckskins, Yount was the prototypical ranger—before the rangering concept surfaced.

Technically, Yount was a “gamekeeper,” paid $1,000 a year for monitoring the park’s wildlife and combating poaching. Rocky Mountain Harry, as he was known, built a small cabin between Soda Butte Creek and the upper Lamar River in the northeast corner of Yellowstone. Along with watching for poachers, he recorded some of the park’s natural history and made meteorological observations.

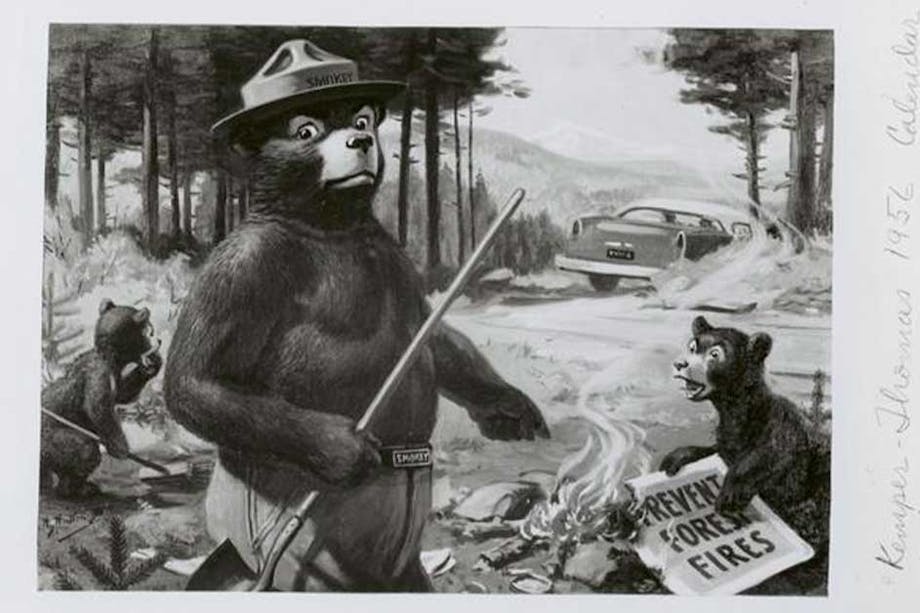

But near the end of his first year as a gamekeeper, Yount resigned, saying the job was too big for one man. “…[A] small and reliable police force of men, employed when needed, during good behavior, and dischargeable for cause by the superintendent of the park, is what is really the most practicable way of seeing that game is protected from wanton slaughter, the forests from careless use of fire, and the enforcement of all other laws, rules, and regulations for the protection and improvement the park,” he suggested in his resignation letter.

Yount’s idea stuck and led to the national park ranger ideal. Today, the National Park Service annually celebrates one of its own with the Harry Yount Award, which goes to “rangers who have the skills to perform a wide scope of ranger duties—protecting resources and serving visitors.”

The First Native American Superintendent of Little Bighorn National Battlefield

It’s been said that Barbara Booher led the second battle of the Little Bighorn. She might have led the third, too.

A woman with Cherokee and Ute blood in her veins, Booher in 1989 became both the first Native American and first female superintendent of what was known at the time as Custer Battlefield National Monument. She then presided over the renaming of the monument to Little Bighorn Battlefield, a move that diminished the appearance that the site was a tribute to General Armstrong Custer. The general, of course, was cut down during the first battle of the Little Bighorn, in 1876.

Critics of Booher’s appointment said she didn’t have the qualifications to be superintendent. But Lorraine Mintzmyer, the National Park Service’s Intermountain Region director at the time, saw not just value in Booher’s Native American heritage but also the skillset she brought to the task. Booher saw her appointment as a chance to tell the battle from the Native American perspective, which had been overshadowed by the interpretive weight given Custer. Her work led to a better interpretation of the site from the Native American point of view, and the eventual placement on Last Stand Hill of a memorial that honors the Native Americans involved in the battle.

“All I’d ever heard about it in school was from the Custer point of view, and when I came here on my own as a tourist in 1973 I thought, ‘Well, that’s all cavalry,’” she once told a reporter. “This is the only place where all the monuments are to the losers.”

From the Little Bighorn, Booher moved to lead the Office of American Indian Trust Responsibility of the National Park Service.

Voice for Desegregation on Public Lands

Desegregating national parks during the era of “Jim Crow,” a period in the 1930s when some U.S. states still maintained discriminatory laws, was a tricky proposition. Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, though an advocate for equality, knew he had to move carefully so as not to lose the support of Southern politicians who held significant influence in Congress.

In 1938 William J. Trent Jr. became Ickes’ adviser on “Negro affairs” and pushed Ickes and park superintendents to desegregate public lands.

He insisted that the Interior Department support “the participation of Negro citizens in all of the benefits of the National Park Program,” urging to remove designations such as campgrounds “for Colored People” from park maps and to desegregate picnic grounds and restrooms.

But his mission was a challenging proposition, for Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia supported Jim Crow laws and expected their laws to apply to the Great Smoky Mountains and Shenandoah National Park, which joined the National Park System in the 1930s.

Little versed in camping or outdoor recreation before joining the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, Trent quickly grasped the potential of the outdoors and wrote an article promoting the benefits of “organized camping” to “adolescent development.”

In January 1939, Trent pushed his demands for equality to a gathering of park superintendents in Washington, D.C., only to see most of them ignore his request. Later that year, however, Ickes implemented a compromise that allowed the removal of segregation signs from Shenandoah National Park and upgrading facilities previously designated for Blacks, laying the groundwork for desegregating the National Parks for future generations.