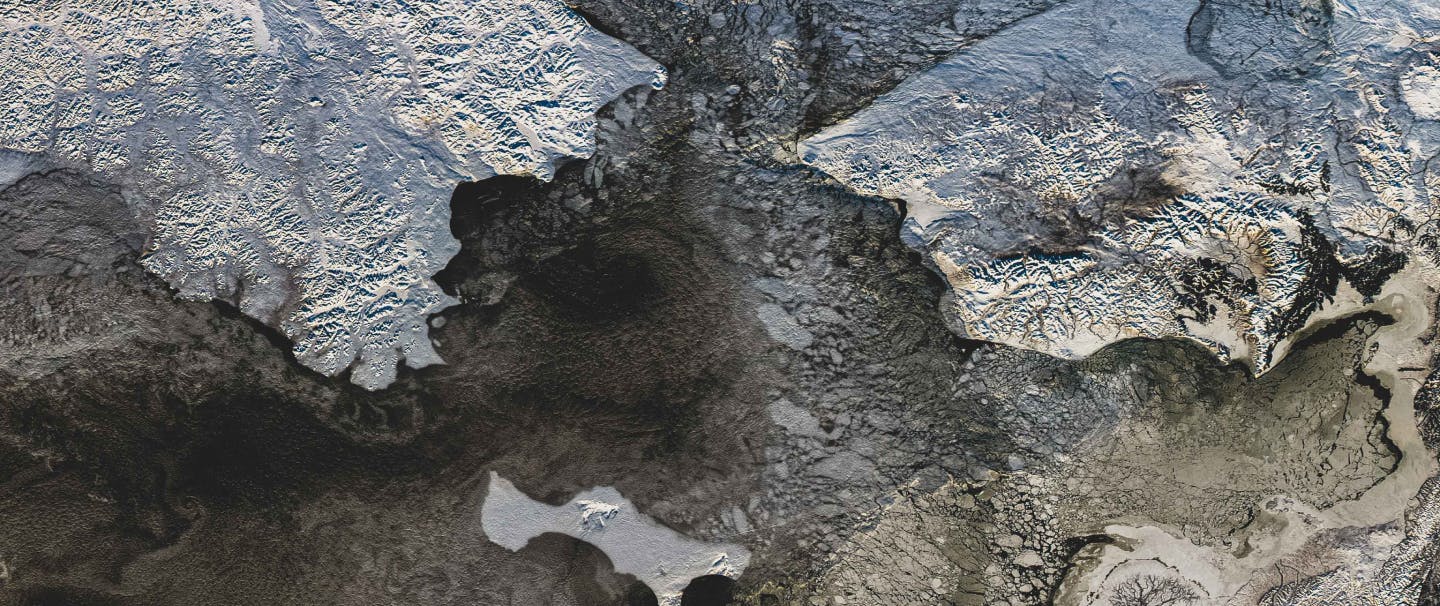

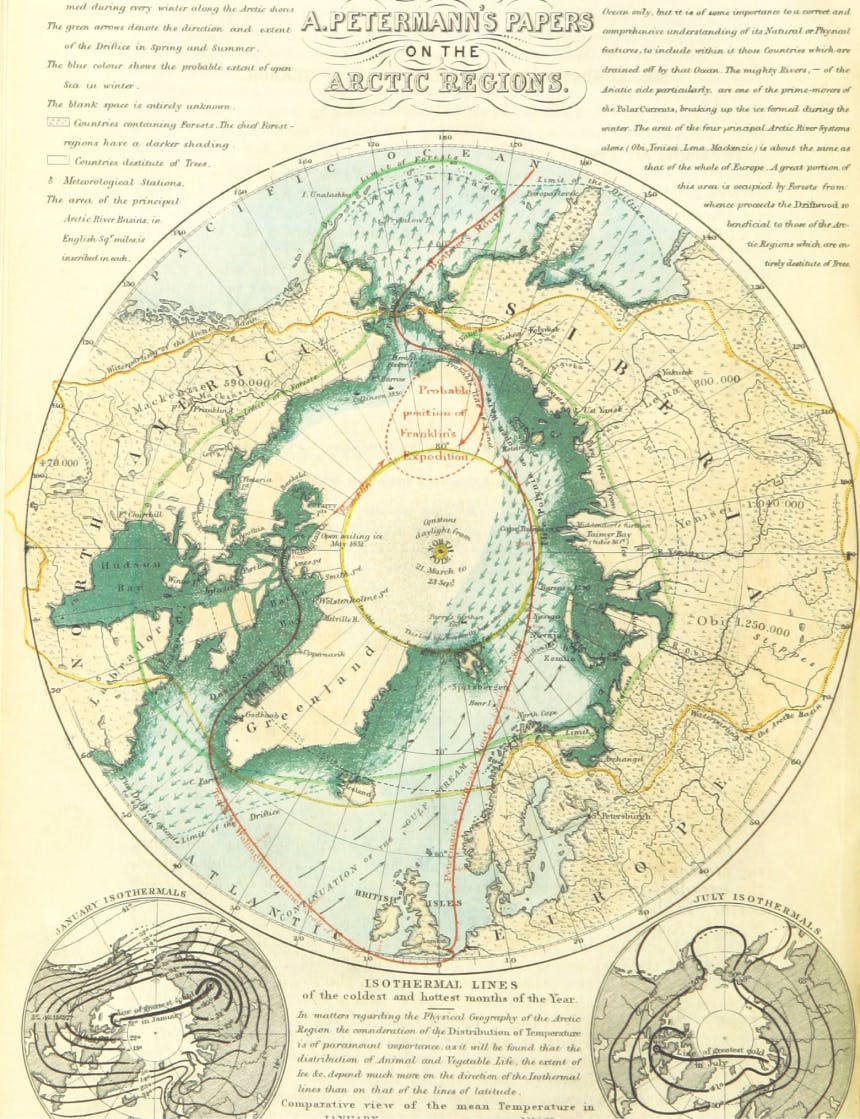

IN THE NORTHERNMOST REACHES OF THE WORLD, JUST A FEW CLICKS SOUTH OF THE ARCTIC CIRCLE, RUSSIA AND ALASKA ARE SEPARATED AT THEIR CLOSEST POINT BY JUST 55 SHORT MILES AND THE FRIGID WATERS OF THE BERING SEA.

It’s believed that a land bridge once connected these two regions, and that 20,000 years ago, humans walked across that natural formation to settle in the Americas from Asia. In the centuries that followed, those land masses slowly pulled apart and became separated by the Bering Strait.

For most of modern history, traversing this passage meant braving the seas — and even then, only when the ever-shifting ice floes would allow it.

But where some saw only unforgiving waves lapping up against the shoreline, a handful of visionary engineers saw a golden opportunity — a crossing that would allow safe travel and even faster transportation between North America and Russia.

The idea of connecting The Last Frontier with Russia dates back to 1892, when Joseph Strauss, project engineer for the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, envisioned a Bering Strait rail bridge. Strauss was heavily influenced by an earlier plan for a worldwide “Cosmopolitan Railway” proposed by William Gilpin, the first governor of the Colorado Territory, which was never completed.

Strauss pitched his idea for this ambitious rail bridge to the Russian government, but the plan was rejected as too costly and dangerous.

A few decades later, following the success of the Alaskan Highway as a vital supply route during World War II, there was renewed interest in creating a similar route even further north. In 1942, the Foreign Policy Association envisioned a highway “near the Bering Strait, linked by highway to the railhead at Irkutsk, using an alternative sea-and-air ferry service across the Bering Strait.”

But concerns over feasibility and cost meant no highway was ever constructed, and the plans were shelved.

Over the course of their journey, they had to ditch a broken sled full of supplies when the drifting ice threatened to take them out to sea faster than they could make their way across.

Although the strait is only 180 feet at its deepest point, the entire route is just south of the Arctic Circle. Construction crews would have to work through extreme weather conditions and freezing temperatures over the course of just five short months, as it would be nearly impossible to continue through the cold, dark winter.

Ice floes also pose a serious risk to any exposed steel, and the areas on both sides of the proposed crossing are extremely underdeveloped. Stretches of the route would have to pass through miles of empty tundra and would require unpaved roads to prevent permafrost.

The lack of a tunnel or bridge hasn’t stopped some from trying to cross, however. In 2006, a couple of intrepid explorers including Karl Bushby, a former British paratrooper, used the winter to their advantage, walking, crawling, and climbing across semi-frozen sections of the Bering Strait as far as they could before enduring countless frostbite-inducing swims into Russian territory.

Over the course of their journey, they had to ditch a broken sled full of supplies when the drifting ice threatened to take them out to sea faster than they could make their way across.

With their rations dwindling, they were resupplied once by plane and again by helicopter — the pilot gently setting down on a fragile sheet of ice for just a few minutes to deliver crucial supplies (and some toilet paper) before leaving the pair alone once again, unable to follow them into Russian airspace.

Fear began to set in that they might become stranded in this no-man's-land — unable to be rescued, too weak to push on toward Russia, and their route back to Alaska quickly disappearing beneath their feet

Karl’s partner, Dimitri Kieffer, was treating a severely frostbitten finger with fistfuls of painkillers, the damage to his hand constantly exacerbated by long, painful swims through the slush.

Fear began to set in that they might become stranded in this no-man’s-land — unable to be rescued, too weak to push on toward Russia, and their route back to Alaska quickly disappearing beneath their feet. But Karl and Dimitri persevered.

After more than 14 days of struggling for every inch of progress, they finally caught sight of their destination in the distance. As they stumbled into the village of Chukotka, two men with no previous arctic expedition experience had done the impossible. They had traveled 150 excruciating miles to become the first explorers to ever walk from America to Russia.