Before there were O’Hairs, there were Armstrongs. And like most homesteaders, the Armstrongs arrived at Paradise Valley, Montana, by way of misfortune looking for fortune. In 1876, Owen T. Armstrong (“O.T.”), aged 27 years old, and Mrs. O.T., aged 26 years old, decided it was time to up and leave Missouri, where they had hewn out a meager existence. Mrs. O.T.’s brother wrote them from faraway Montana Territory, regaling them with tales of running cattle year-round without supplemental feed. “Perfect cattle country,” he wrote. His letters convinced O.T. and Mrs. O.T. to make their choice and take their chances. They loaded two covered wagons with tobacco, bacon, beans, apples, lard, a rifle, yarn, and other supplies, and drawn by teams of mules, they embarked across an ocean of grassland for Montana Territory, their two small children and an adopted boy of 12 years old in tow.

They passed through Missouri to Junction City, Kansas, steadily pointing their team west through Nebraska via the Oregon Trail and kept onward to Cheyenne, Wyoming. Rather than cut north to Montana Territory on the Bozeman Trail, the Armstrongs instead traced the southern border of Wyoming Territory into Idaho Territory. The center of Wyoming Territory at that time was not safe for wagon trains as it was just a few years after the Battle of the Little Bighorn and tensions were running thick between Tribes and Euro–American settlers pushing by the dozens westward. So, the Armstrongs took the old stagecoach road from Fort Hall, Idaho, north to the gold mining town of Virginia City, Montana.

Mrs. O.T. fastidiously kept a daily diary on the trail, recording things like the weather, wildlife sightings, livestock health, their passing through ghost towns, ferry tolls, layover days for washing and cooking, and the road conditions: “Crossed the creek this morning. Water ran into wagons and mud deep on both sides … Went 8 or 9 miles and mired in the mud … Lost shovel out of wagon … The buffalo gnats have tormented us all day.” Flowery landscape descriptions and especially feelings never touched the pages.

After three months and 1,400 miles of plodding along in a wagon train, they reached their destination: Paradise Valley, Montana Territory. Mrs. O.T. claimed that by the time they had reached their home site, the children had ridden in the wagon for so long that they had forgotten how to walk.

The Armstrongs bought a ranch about nine miles south of present-day Livingston, Montana, along a spring and just on the west side of the Yellowstone River. The east side of the Yellowstone River was designated Crow Territory and per treaty terms, homesteaders were not allowed to stake claims there. They built a small log house, which still stands to this day. To reach the upper floor where everyone slept, they had to go outside and climb a ladder to the second-story window.

The Armstrongs were credited with bringing the first registered cattle (meaning purebred cattle, with documented pedigrees) into the Valley. In the 1890s, O.T. bought his first Herefords in Bozeman and Kansas City. Soon after, he rode to White Sulphur Springs and bought two bull calves. He didn’t actually have enough money to pay for the stock, but the fellow selling told O.T. to take them anyways. He figured anyone willing to ride that far to drive two bulls back to Paradise Valley had to be honest. O.T. trailed the bulls home and mailed the remaining payment to White Sulphur Springs. The rest of the cattle were trailed to Armstrong’s place from A.B. Cook Ranch in Townsend, Montana.

The Armstrongs found Mrs. O.T’s brother’s claims of “perfect cattle country” to be partially true. Because of the wind howling through Paradise Valley, snow didn’t stick to the high ridges and it kept the range exposed. But soon, the Armstrongs figured out they couldn’t run cattle year-round without supplemental feed. It became clear they needed to irrigate fields to raise hay for feed. O.T. began building a canal for flood irrigation, Armstrong’s Ditch, which he worked on for years and which today still diverts water from the Yellowstone River to ranchers throughout the Valley. The Park Branch Canal, as it’s now known, can need some riprap and repair from time to time to hold up eroding banks, but ranchers can still count on getting their water from here.

Most would agree it took a big man in a tough place to homestead in Montana. Wild game was the main food source for many of the earliest Euro–American pioneers. Steam and hydraulic tractors wouldn’t arrive in this corner of Montana until the 1920s, and even then, many continued to use horses, oxen, and mules. Irrigation ditches had to be dug with a scoop shovel. Electricity wouldn’t reach Paradise Valley until after WWII. Telephones arrived in the early 1960s. Supplying the larder with flour and sugar, socializing, and educating children all presented challenges in those earliest years. As luck would have it though for the Armstrongs, there happened to live a doctor across the river, on the Crow side. When a horse stepped on his six-year-old daughter’s leg and broke it, O.T. rode to the edge of the river and shot in the air.

“An old man come to the edge of the river. O.T. pointed to the doctor’s home and then to himself. The old man ran up and got the doctor. The doctor had to ride to … Carter’s Bridge and catch a ferry and then ride to the ranch to set Grace’s leg,” recorded one of O.T.’s sons.

The next four generations of Armstrongs expanded the family substantially, as did the marriages of those children.

“My dad, Allyn O’Hair, came from Dakota and was a young man working in Terry, Montana,” explained Andy O’Hair, the fourth generation to live on the ranch. “He had worked in threshing and sheep shearing and arrived here to work on the Armstrong ranch in 1931, during the Depression. He rode by freight train, switched out at Livingston, and got here on the caboose of the Park Branch Line. The conductor found him and asked for his ticket. Dad said, ‘I’m sent C.O.D.’ They let him off. It was 30 below that day and he walked two miles into the ranch to get his job. He was 20 years old and desperate for work. My mother, O.T.’s granddaughter, Agnes Armstrong, was still in high school. Dad worked here one summer and then they let him go. Then they called him back. He came back and went to work herding cattle here for the Armstrongs. In 1936, he married my mother, Agnes.”

As soon as Allyn and Agnes took over the ranch, the place was known as O’Hair Ranch.

“Labor on ranches has always been a situation. I can remember my dad having a hard time finding hired hands. Part of his success was due to the people he was able to hire. He had some awful good people working for him. We inherited some of that for awhile,” said Andy.

Allyn O’Hair’s approach to the labor situation was to hire old drunks hanging around the bars of downtown Livingston.

“He’d go to the bars and get these guys out and he’d make them irrigators. He’d buy them boots, shovels, whatever they needed. They came out to work for a month or all summer. If he lost one, he’d go back to the bar and find another one. Agnes cooked for all of them. Some of the hands they hired, it’s a wonder these O’Hair boys turned out at all,” said Karen O’Hair, who married Andy after they fell in love as teenagers on a pack trip up to Electric Peak.

“We were married in 1964 and I moved onto the ranch,” Karen explained. “I had to have a cowboy. He had to love horses as much as I did.”

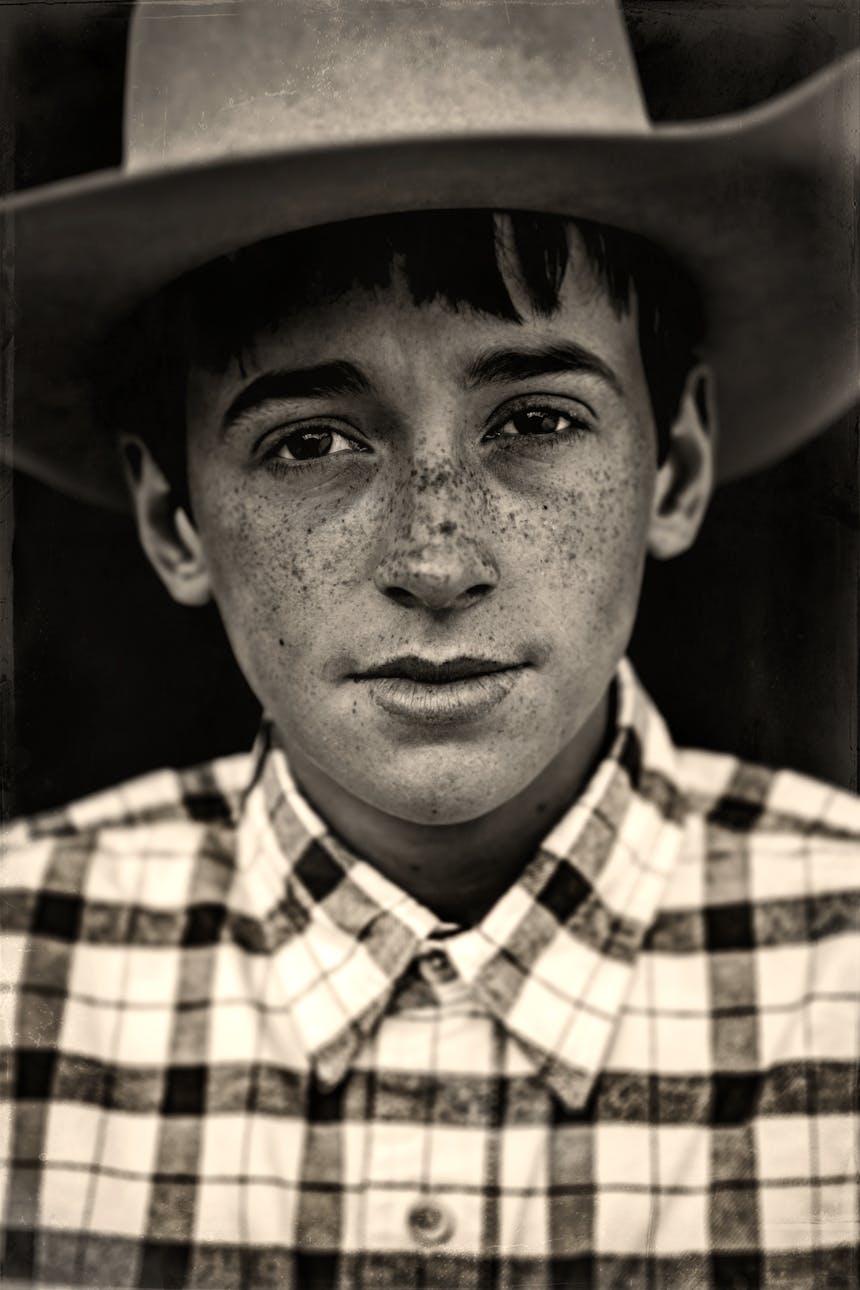

Today, the sons and grandchildren of Allyn O’Hair and Agnes Armstrong live on the ranch, representing a Montana legacy six generations deep. They occupy houses and cabins that were built and then moved around by teams of horses atop rolling logs long ago. They work cattle across the same land O.T. Armstrong worked cattle more than 140 years ago.

“As a rancher, you have to adapt to the times,” said Andy. “We use pivot irrigation instead of flood irrigation. We switched from Herefords to Angus in the 1970s. Hired hands are even harder to find these days. They want too much and they don’t want to work as hard as we’re doing it. But we’re still here. Everyone in the family holds interest in the ranch and we all work together to run it. We don’t interfere with the way another person does things. We ask how we can help. The youngest generation of the family has expressed interest in carrying on with this. That’s the best thing we could ask for.”