Sitting like stone guardians just below the Canadian border, the North Cascade mountains are keepers of the wildness that once roamed unchecked across North America. Soaring high into the skies, their stony and snowy peaks seem to scrape at the clouds that pass overhead demanding tribute as they float by. Sparkling like scattered gems, glacially fed lakes brilliantly reflect the sunlight while, through deep green valleys, bright, blue-gray rivers run down to the surrounding flatlands. It is a spot where a person could quickly leave behind all of the trappings that attach themselves to our modern daily existence and transport to another existence entirely.

Roughly 90 million years ago, the range began to take shape when two continental plates collided. The force caused parts of the North American plate to begin to jut upwards, reaching for the sky. It created volcanos, still active today, that form part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, along with the rest of the Cascade Mountain range. The area is still dominated by huge granite deposits, remnants of mountains that eroded away 5 or 6 million years before now.

The first humans started showing up in the area around 10,000 to 15,000 years ago. They were part of a great migration of people moving north as the last Ice Age at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch was winding down. The retreating glaciers that had blanketed the area left behind rich soils for planting; there was thriving wildlife and lush valleys to support it. The humans flourished, and looked upon the surrounding peaks as the realm of gods and giants.

The indigenous peoples formed different tribes based upon where they settled and lived their lives. Sometimes the tribes would work together; sometimes they wouldn’t, and hostilities would commence; but, through it all, they respected and lived off the land. Today there are over 160 archeological sites that give some insight into what their lives were like. Plus, the tribal governments of the Upper Skagit, the Suk-Suiattle, and the Swinomish, along with the Nlakapamux First Nation of British Columbia, maintain their presence in the land that they filled with their ancestors’ spirits.

European explorers caught glances of the mountainous area from afar as they explored the region from the decks of ships traveling up and down the coast. It wasn’t until an intrepid fur trader named Alexander Ross arrived in 1814 that the stronghold began to yield to the outside world. He said of his trip: “A more difficult route to travel never fell to a man’s lot.”

Part of the beauty and mystery surrounding the North Cascades comes from their relative remoteness and forbidding terrain. Located far enough from the coast that real effort was required to gain access, the area was able to avoid the mass migrations that plagued so many other areas of the American wilderness. Some gold was found, but not enough to drive a rush like those that hit the Sierras and the Rockies. Short weather seasons coupled with unpredictable weather conditions and difficult transportation conspired to keep invaders at bay. As people headed for the farmlands to the east, the shorelines to the west, and the less inhospitable mountains to the south, the North Cascades were ignored, bypassed, and left alone.

But there are cities and towns there today. People live on the slopes of the behemoths that touch the sky. They hike through the never-ending valleys, scramble up steep slopes, paddle across sapphire lakes and run the rivers. They mingle amongst the wildlife that populates the region and follow in the footsteps of those that came before.

Luckily, a host of people, groups, and government agencies, in both the United States and Canada, recognized what magic the mountains held and came together to set up numerous protected areas to ensure minimal despoiling. There was some logging and mining, but the scars they left behind are faint and continue to recede yearly.

“It’s a rugged, wild playground

fit for humans to explore

with room enough for animals

to exist and thrive”

Initially proposed to be one of the first National Parks alongside Yellowstone and Yosemite in 1892, it took until 1968 for the North Cascades National Park to be established. During that time, the natural beauty emanating from the region brought together a wide swath of individuals and groups to advocate for the creation of a park. The Mountaineers, a Seattle-based climbing club, started lobbying for it at the beginning of the 20th century. Forester and wilderness advocate Bob Marshall argued for it in the 1930s before his untimely death. The Sierra Club waded in during the 1950s, and the timeless images of Ansel Adams introduced a region nicknamed “the American Alps” to the nation.

Today, it is part of the sprawling North Cascades National Park Complex. Comprising the North Cascades National Park along with the Ross Lake National Recreation Area and the Lake Chelan National Recreation Area, it covers almost 700,000 acres of pristine wilderness. When you pair that with the nearby Mount Baker-Snoqualmie and Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forests, there are over 2 million acres of land that closely resembles what the area has looked like for millennia. On the Canadian side of the border are several more provincial parks and recreation areas.

“Due to the remoteness of many areas inside the complex, you get a solitude that is sorely missing from most parks these days,” says Katy Hooper, a park ranger stationed there. “When you head into the Steven Mather Wilderness areas inside the park, you do it on foot; roads are at a minimum. From the moment you head in, you feel yourself lost and transported away.”

Filled with virgin old-growth forests that have never seen an ax, the area boasts massive stands of trees that extend as far as the eye can see. Running like a crown molding around the park are the sub-alpine meadows teeming with the last visible vestiges of growth before the looming vertical walls of the myriad summits that crown the park. Weaving throughout the entire region are the glaciers, remnants of the last time this region, and the rest of the globe, was shrouded in snow. You have to go to Alaska to find another area more densely populated by glaciers in the United States. Fed from the booming winter storms rolling in off the Pacific, they are struggling to survive in this ever-warming world we live in.

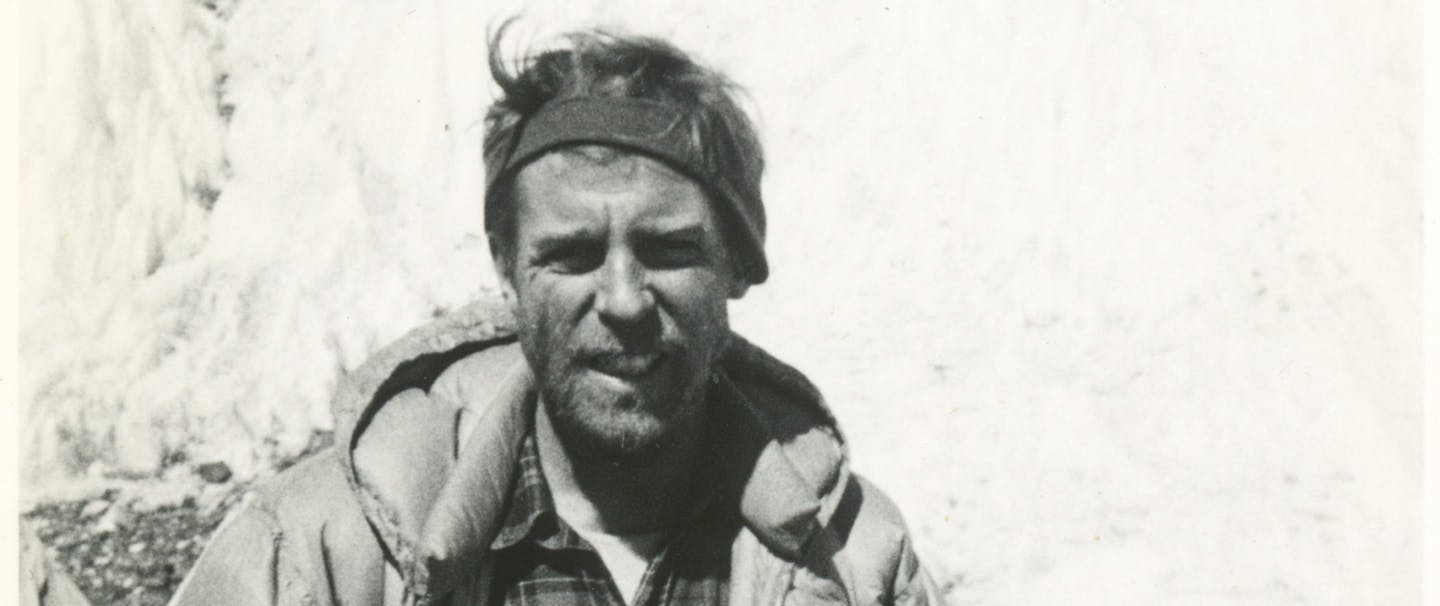

The beauty and remoteness of the park and surrounding terrain call to many who are looking for somewhere to recharge their souls. In the late 1930s, climber Fred Beckey, then in his teens, began roaming the mountains with his local Boy Scout troop. Soon he was figuring out ways to stand on top of the many peaks that surrounded him. He would go on to dedicate his life to opening up the mountains, stringing up an amazing array of first ascents throughout the North Cascades. In his footsteps would follow more climbers and the area is now regarded as one of the premier high alpine climbing regions in the world, regularly attracting the best from across the globe.

But not all are drawn into the thin air and the bleak landscape above the treeline. Due to the many glaciers throughout the region, there is a continual downhill flow of fresh, pure water—hence the name Cascades. With over 250 high alpine lakes and a plethora of creeks, rivers, and streams, it’s a serene and vivid environment adored by water-lovers. Hordes of salmon arrive each season heading to their spawning grounds, trout of all stripes swim along just waiting to battle an angler, and wildlife congregate along the banks awaiting dinner.

While they watch and wait, recreationalists zip by in canoes, on rafts, and in kayaks, navigating through tricky shoals, raging rapids, and long stretches of placid water. In the winter, when the sun leaves the sky earlier and the clouds turn charcoal-gray, skiers traipse through the backcountry in search of fresh Pacific powder or rip groomers at Mount Baker, Snoqualmie, and a host of other ski areas.

Beyond providing thrills, the North Cascades are also known for recharging souls and providing artistic enlightenment. In 1952 soon-to-be Pulitzer Prize-winning Beat poet Gary Snyder spent a season atop Crater Mountain working as a fire spotter and writing. Not long after him, his friend Jack Kerouac headed into the woods in 1956 to work as a fire spotter at Desolation Peak, in a cabin that still stands today. As he spent his days in quiet contemplation, he was inspired to start writing. From his efforts came major portions of his books Desolation Angels, The Dharma Bums, and Lonesome Traveler. In The Dharma Bums he wrote: “Mad raging sunsets poured in seafoams of cloud through unimaginable crags, with every rose tint of hope beyond, I felt just like it, brilliant and bleak beyond words. Everywhere awful ice fields and snow straws; one blade of grass jiggling in the winds of infinity, anchored to a rock.”

But while humans are relatively new to the area, its original inhabitants, the wild creatures, continue to thrive, with relatively minimal human interactions, as they have throughout the ecosystems found in the North Cascades, since long before the arrival of man.

The massive ridgeback of peaks that makes up the North Cascades acts as a giant rain screen leaching any and almost all moisture from the clouds that regularly roll over the area from the nearby Pacific Ocean. This line of demarcation, along with the dramatic rise in elevation from valley floors to summits, has created an area that is complex and wide ranging. Scientists have identified eight different ecological zones with distinctive flora and fauna.

The rainforest regions of the western mountains are characterized by a lushness that is loaded with vibrancy and denseness. Sidestep to the east, in the ever-present rain shadow, and high desert conditions exist. Gone are the ferns, western hemlocks, red cedars, and red alders, so prevalent just a few miles away. In their place are whitebark pine, Engelmann Spruce, lodgepole pine, and huckleberry, covering the slopes. Visitors can find the sudden terrain shifts disconcerting, to say the least.

Roaming throughout are the true residents of the North Cascades—a healthy and growing pack of gray wolves, or timber wolves. These apex predators once held sway over the entire continent from Alaska to Mexico, until they were hunted almost to extinction. Here, hidden from prying eyes, lynxes, bobcats, wolverines, and cougars carve out territories in the remote and rugged terrain. Grizzly bears roam north of the border in Canada and many think that it’s only a matter of time before they take up residence farther south.

Of course, the reason that all of these predators survive so well here is the preponderance of other animals to help feed them. Mule deer, elk, and moose can be found slowly meandering through fields, while, high on the slopes, marmots and mountain goats scamper over wind-blasted rock faces and fields of talus. Over 200 bird species soar overhead, 28 species of fish splash along, 21 reptile species slither and slink underfoot, while a dozen different types of bat take flight at night, and over 500 different types of land insect live on all types of substrates.

“It’s a rugged, wild playground fit for humans to explore with room enough for animals to exist and thrive,” says Christian Martin of the North Cascades Institute, a 33-year-old organization dedicated to protecting the region and introducing people to it. “It’s the wildest place you can find in the Pacific Northwest.”

Perhaps the most emblematic examples of the interactions between the modern world of man and the more elemental one of nature are the towns of Leavenworth and Stehekin. They are both dissimilar and similar at the same time. Tourism is the lifeblood that keeps both alive and healthy, yet their approaches to it are polar opposites.

Located on the north end of Lake Chelan, the tiny community of Stehekin has only 75 permanent residents and is accessible only by boat, plane, or foot. There are no roads leading in. Resembling a northern fjord more than a mountain lake, it draws its beauty from the dramatic mountains plunging into the placid waters and can easily take visitors’ breath away. It serves as a base camp for adventures into the surrounding hills and a launching point for treks into the Lake Chelan National Recreational Area that envelops it.

At one time Leavenworth was home to the second largest sawmill in the state and thrived as a logging and mining community. All of that changed when the railroad was relocated in the 1920s due to the dangers of routing trains over nearby Stevens Pass, the site of numerous deadly avalanches and nowadays a thriving ski area. The loss of the railroad coupled with the Great Depression left the town in shambles.

Its rebirth began with the return of soldiers from World War II: they recognized how closely the surrounding area resembled the Bavarian villages in which they’d been stationed. They convinced the city governors in the early 1960s to completely renovate and turn their hometown into a carbon copy of a German mountain town.

Visitors today are greeted by locals dressed in Lederhosen, with bulbous steins of beer, nonstop brats, and continual Bavarian music. While the illusion is impressive, what really makes everything click are the glistening river teeming with trout, the world-class climbing just up the road in Icicle Canyon, and the myriad other endeavors just steps away.

If there is one thing that the North Cascades have been able to do, it’s keep the intrusions of modern man at arm’s length. Yes, there are our fingerprints throughout the region, but they tend to fade quickly as the weather and ecosystems diligently wipe them away. It’s a spot where it’s possible to get a glimpse of the magic and beauty that Mother Nature has wrought—and to truly appreciate the protection she has bestowed on the region over these last few centuries.

Traversing through its borders, one is able to feel the elemental components of our own existence. For a brief few moments, you can understand how privileged you are to have been able to intrude upon this relic of an older and simpler time. You are in the wild.