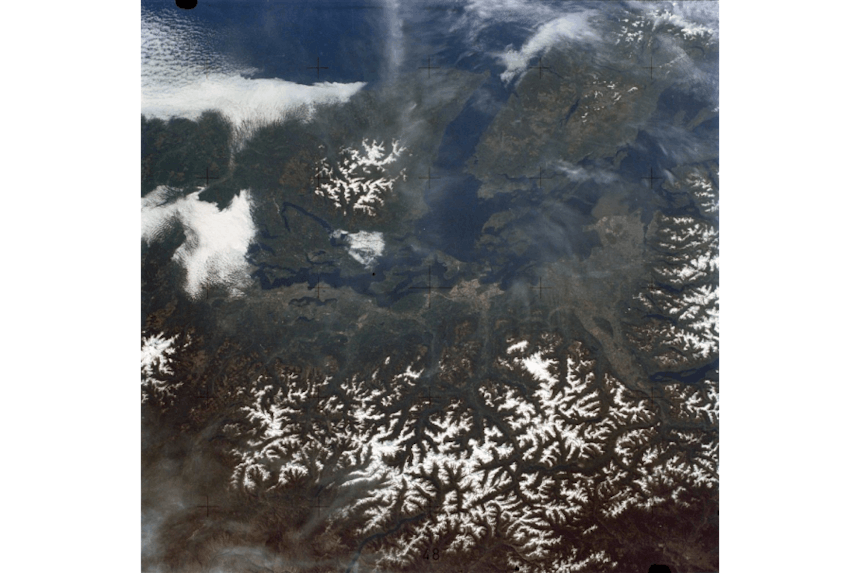

North Cascades National Park counts more than 300 glaciers along this northwestern spine of mountains—and that’s just inside the park boundaries. The North Cascades are the most glaciated place in the country outside of Alaska, but this ice-clad range has remained relatively under the radar compared to places such as Montana’s Glacier National Park or Mount Rainier in the South Cascades. The landscape here feels wilder, at the edge of things, with a mystical feel of vastness and geologic time lent by the presence of these relics from the last ice age.

Glaciers define this part of the world. The radiating deep blues of their seracs and crevasses, the jagged icefalls, the muted grays and browns of a retreating terminus and the white beckoning vastness of their snow-covered expanses have drawn some of the most creative adventurers of our modern era to document them at this moment in time, in ways both unique and in homage to the distinct character of these mountains—before the glaciers retreat entirely and disappear.

Photo provided by: Jason Hummel

THE GLACIOLOGIST

Mauri Pelto isn’t sure which came first, his love of snow or his love of skiing. The former cross-country ski racer knew he wanted to spend his life amid the product of winter, but it wasn’t until he met his first glacier in Alaska that he understood he would also spend it with these ancient ice behemoths that mesmerized him with their dynamism—and that he would use skis to get to them. He’s now 37 years into a 50-year project to document the movement of glaciers across the entire range of the North Cascades.

Forty years ago, glaciology was a niche science, and the United States Geological Survey was only documenting one glacier per mountain range. When, in 1983, the National Academy of Sciences made it a high priority to monitor glaciers across a range and see how they respond to climate change, Pelto rose to the challenge. He chose the North Cascades, where most glaciers lie in wilderness that requires hiking, versus wheeled vehicles or helicopters, to access. He narrowed his study to 50 glaciers that he would visit periodically, and ten that he would return to each summer for half a century, becoming more familiar with their characteristics and movements than many of us are with our closest friends.

Photo provided by: Jason Hummel

Pelto did almost all his research on skis in those early years. In the absence of GPS, a cell phone, or a 24/7 connection to forecast weather in the backcountry, he honed his topographic skills and brought along an altimeter—which doubled as his barometer—and read clouds to create his own forecasts for his stints in the wild. Now, he’s largely abandoned skis as the snowpack has dwindled (and the alder bashing becomes more frustrating with long skis in hand), and he uses more updated technology, but his process is the same: measure the terminus, measure the streamflow below the ice, then hike onto the glacier itself and measure the snow depth, tossing ropes down crevasses and driving steel probes through the snowpack.

“This personal relationship adds a deep understanding,” Pelto says.

“If you don’t visit the glacier, if you just look at it from a map or base evidence on a model, you’re not going to understand why

it’s changing the way it is unless you’ve put in the time with the actual thing you’re observing.”

THE ARTIST

Jill Pelto first accompanied her father on his glacial studies at the age of 16. Growing up in Massachusetts (Mauri makes his pilgrimage west from there each summer for his studies), nothing to prepared her for the scope of this sight so far outside her familiar. Her desire to communicate its effect—the awe, how much she loved this gigantic landscape that was so different, even the overwhelming physical challenge—is part of what drove her to a double major in climate science and fine arts.

Now, Jill Pelto’s art reflects her uncommon brain that straddles the scientific and the artistic: her paintings interpret what’s happening in our environment, marrying the data of graphs with the ethereal and visceral images of watercolor.

Artwork provided by: Jill Pelto

Take Decrease in Glacier Mass Balance for example, a series of swirling blue and brown prisms falling down the craggy points of a graph line that matches ice loss over decades. She’d just come back from a field season in the Cascades with her father in 2015. That year, the impact of drought and forest fires on the glaciers struck her; she painted this piece to communicate how drastic the change in ice has been, a beautiful story that people can actually relate to far more than characterless points on an XY axis. At the same time that it delivers an environmental message, the painting evokes the magnificence of the volume and height of the ice, the feel of such thickness towering above your head.

Ultimately, Jill Pelto’s art is about making connections for people. And while she’s since been to glaciated massifs and expanses from New Zealand and Antarctica to British Columbia, she returns without fail to the North Cascades. “You’re out there surrounded by ice and snow, but also lush rainforests and flowers and wildlife, and you can’t help but link the glaciers with the impact they have on the surroundings. For me, that’s the biggest piece of why I love being there: being a part of this world that they have created.”

THE AVIATOR

Nearsightedness was nearly the death knell of John Scurlock’s dreams. From as long as he could remember, he had imagined being a pilot in the Air Force, flying fighter jets—until his poor vision was measured in third grade. The dream faded. He got into climbing and backpacking instead, became obsessed with maps and guidebooks, and developed a talent for photography.

Then, in his 30s, on the advice of a friend, he checked into the claim that one can’t fly without perfect vision. It turned out to be a myth, and Scurlock got his longed-for pilot’s license.

“I remember when I first started flying around Mount Baker, which is a significant deal to head out there in the dead of winter. I remember being rather astonished at what I was seeing, that it was unbelievable. In climbing or backpacking, I’d never seen it in those conditions. It’s just marvelous, snowy mountainous terrain stretching out toward the horizon.”

He began flying and photographing as obsessively as he’d pored over maps and guidebooks, between stints as a flight paramedic in Skagit and Whatcom counties. Word of his work and experience spread, so that eventually he was taking aerial photographs for USGS projects and university glaciologists studying the Cascades glaciers. “That led to a project where I wanted to photograph every glacier in the lower 48 states,” he said. Scurlock has flown and shot glaciers from the Sierras in California and Glacier National Park and the Beartooths in Montana to the Bighorns and Winds in Wyoming and all the glaciers on the fourteeners in Colorado.

But, like Jill Pelto, he’s still drawn back to his home range above all others. “I ski a lot and you think you’re familiar with the mountains. And then you look at how narrow your winter view of them is comparatively,” Scurlock says. “I had a sense of wonder about it back then and I still do to this day.”

Photo provided by: Jason Hummel

THE SKI MOUNTAINEER

“It’s almost unfair to be forgotten and not even remembered,” declares Jason Hummel.

The accomplished ski mountaineer isn’t talking about himself. Instead, he’s referring to the Cascades glaciers and his quest to ski and photograph all the named glaciers in the range. It’s not a typical ski mission; it’s not about the lines or snow quality or even the fact that his objectives happen to be first descents. In fact, Hummel has a hard time finding other skiers to join him on his outings, which can appear to the untrained eye as suffer-fests for little reward.

This is about telling the stories of these places that no one’s really been. Very few people have touched the fringes where these glaciers reside.

Hummel grew up next to Mount Rainier, where ski mountaineering became second nature to him. After climbing Mount Adams more than 60 times, he started thinking about ways to see things anew. He began circumnavigating the peaks, then traversing one part of the range to the other, tying it all together. And then he thought, “What glaciers have I missed?”

The origin story of Hummel’s Glacier Project came in a challenge to himself to move away from following the standard paths. “It became a reason to go out to these obscure weird places on the backside of a mountain you’d never go to. Hike 20 miles, go off the back, and then go another 30 miles through savage terrain to a whole new piece of terrain. I started to see places no one had ever seen before, or that only the original parties from 100 years ago had seen.” And as he was the only one bearing witness to the landscape on such a scale, Hummel wanted to document this point in time, these glaciers, as they are now.

“It’s hard to imagine the kind of change where glaciers are gone from these mountains. Picturing Mount Olympus without its 3,000-foot blue glacier, that’s a powerful thing,” Hummel says. “But for any generation, the new normal is just normal. Olympus will still be there, it will just be different.” But Hummel’s project will be the snapshot of his own normal for future generations.

Photo provided by: Jason Hummel

THE FUTURE OF THE CASCADE GLACIERS

There’s no question these glaciers are in retreat. Mauri Pelto has camped in the same spot to study the Easton Glacier for decades. In 1990, that spot was a stone’s throw from the terminus, the sounds of the restless ice and the meltwater stream flowing from its icy underreaches serving as constant background music. Fierce downslope wind from the glacier chilled the air and shook the tent violently, making it feel more like the harsh Alaskan tundra than a campsite an hour outside Bellingham, Washington.

Today the Easton has retreated almost half a kilometer, pulling back from this little side valley to become a relatively distant presence. With the ice has gone the wind, replaced by typical summer bugs, and gone now too is the meltwater stream. Three of the glaciers that Mauri Pelto started with have vanished in the last three decades.

“With our current climate, we’re going to lose at least 70% of the glaciers. With another degree of warming, we’ll lose all of them.”

But, he says, “vanish” is a relative term in the slow time of geology; it will take a lifetime or so for all the small glaciers to disappear from these mountains.”

As they retreat, the landscape changes in their wake. New alpine lakes are formed. The barrier from civilization that glaciers provide to wildlife like grizzly bears and mountain goats shrinks. Their meltwater will no longer swell the volume of streams and rivers. The treeline will rise in their absence.

“Think of it like your favorite beach, and sea level rise takes it away; or your favorite lake, and some big business comes in,” Mauri Pelto says. “You lose something that’s natural and beautiful and a resource. When it’s gone, there is something else there, but it’s not that. You’ve lost a dimension of the landscape, and that is nearly impossible to replace.”