Reflection by Deenaalee Hodgdon

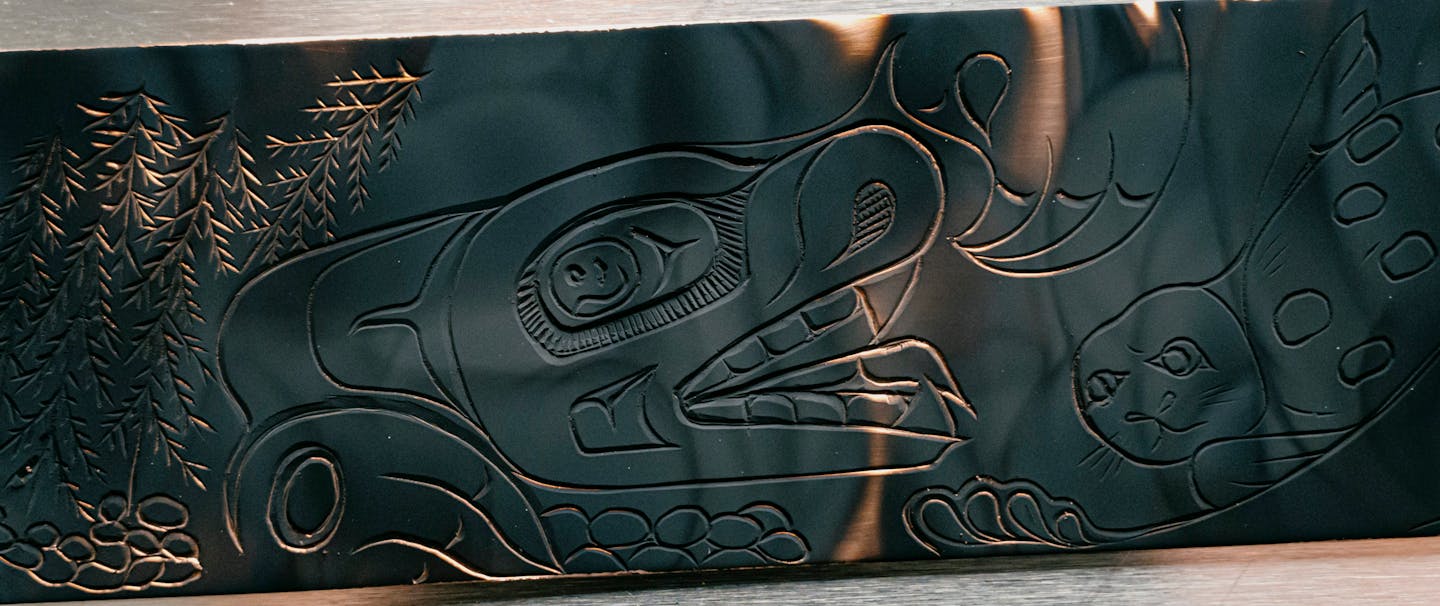

Carved into silver, the fiddlehead catches my eye as light reflects off a displayed cuff’s surface. We are standing in Mary Goddard’s studio in Sheet’Ká (Sitka), Alaska. On the wall, seemingly fresh splotches of paint sample shades of green that seem to bring the most northern rainforest into the small space. Copper sheets, large unfinished tina’as, and a formline eagle and raven sit waiting to take flight on her worktable.

“The cuff’s color will shift according to the wearer’s pH levels” Mary tells Kiliii Yuyan and Nels Evangelista, two of the creatives on our team, as we eye a number of the metal bands sitting on a cloth bag. “These are my in-laws’. My father-in-law never takes his off, and you can see how his pH has changed the metal.”

As I eye the plate of copper sitting on her workbench, I wonder vaguely what color it would turn after years of interaction with my skin. It seems like the ultimate way to customize a piece of jewelry, a story to be told under the influences of the original artist, ore, and wearer.

It is clear that Mary (Tlingit-Kaagwaantaan: Eagle/Brown Bear) is a storyteller. She etches spoken word, passed on through generations and translated through dreams, onto the metals of the earth. Engraving stories into copper and silver offers the continuity of traditional formline designs evolving to meet the contemporary. The fiddlehead cuff is an example of this, featuring plant life as the central character as opposed to the animal life that is often thought of in Pacific Northwest formline work. Conversations and critiques of the past and present are interwoven with roots, porcupine quills, and speculations regarding the future, such as in her 2017 cuff titled “Selling Alaska,” which speaks to the transfer of Alaska from Russia to the United States, which took place in Sitka.

Worn on the wrist, hung from the ear, kissing the neck, Mary’s pieces are focal points that draw the eye. Copper catches crimson midnight sunsets. Patinaed silver—the hue of the ever-shifting ocean prisms. These are stories from the lands and waters of Southeast Alaska depicting the plants, animals, and Peoples that call them home.

The day after we meet Mary at her studio, we head to the Alaska Raptor Center to check out her most recent installment. The center lies on 17 acres of temperate rainforest along the Indian River. It’s picturesque, to say the least, with yellow cedar and Sitka spruce creating a canopy above and the smell of budding skunk cabbage and devil’s club permeating the air below. We pull up our hoods as the rain lazily drizzles down while we make our way down a gravel path.

In 2018, Mary hosted her own photoshoot here to feature a collection called Tlingit Legends. Tlingit Legends is regalia at its finest, a collection of jewelry crafted by Mary’s hands, featuring Mary’s husband, Lucas, and sister, Samantha, and shot by photographer Christal Houghtelling. The photos were then compiled into a journal sitting alongside their origin stories written in Mary’s words.

Though her jewelry is what we came here to feature, it is clear as our conversation unfolds that storytelling in this form is just one aspect of her life. Like many Indigenous artists, she applies a holistic approach to her trade— during the day she serves as a regional catalyst for the Sustainable Southeast Partnership, forming relationships with surrounding Southeast Alaska communities to build opportunities for regenerative, culturally relevant tourism. With her husband, Lucas, she helped build Waypoints for Veterans, a path for veterans and emergency responders to connect with the outdoors through a variety of activities, in community with one another. Mary’s artwork transcends the jewelry-making space, bringing stories to life through film and nurturing the bellies of the people by foraging and preparing foods gathered from the land and sea, such as those ever-present fiddlehead ferns, watermelon berries, deer heart, venison, salmon, and shellfish. Check out her most recent article in the Spring 2021 issue of Edible Alaska magazine here. As she speaks to all these projects, her son, Ryker, joins us, promptly showing me the corner of the house he has converted into his own bunkhouse, and I am left wondering, how does she juggle it all? The art, her businesses, community organizing, and being a mother?

As we emerge from the undergrowth, we are greeted by a clearing of muskeg. “That is where we shot Tlingit Legends with the snowy owl,” Mary recalls, gazing out over the tufts of moss that remind me of the tundra that I call home. We stop our slow migration down the path in front of a cedar bench. It’s a little over six feet in length, its width the expanse of a tree that has seen many turns around the sun. Centered in the middle are an eagle and a raven. Juxtaposed against the soft mustard yellow of the cedar, the copper plating is vivid and sharp, and I meditate on the question of how these two will grow old together in their new state of being.

The bench is a collaboration between local Sitka artist Zach LaPerrière and Mary.

“It felt like it needed balance,” Mary reflected. “I was like, ‘Zach, what do you think if we propose a raven … add a raven and do the lovebirds, which is symbolic in Tlingit culture of balance.’”

It seems like the perfect union of story, artistry, and collaboration. In a time of division in the community through coronavirus mandates, political estrangement, and racial reckoning, the conglomeration of wood and metal brings a sense of hope for communion.

On our last night, Mary, Lucas, and Ryker come for dinner to our Airbnb. They bring the whole nine yards, from deer backstrap to last season’s salmon, bottles of wine, and, of course, freshly picked fiddlehead fern salad—One cheese-filled and a dairy-free option. This is hospitality.

And so, as we always have done, we sat, visiting and feasting into the last night. It’s late spring. Mixed with the more southerly latitude, it still gets dark out, and as the tide rises, the sun sets on our last night with Mary, Lucas, and Ryker in Sitka.

As we wrap up our feast and leave our stories with hooks and laughter, Mary whispers in Ryker’s ear. He comes back moments later with two handfuls of gift bags, delivering each, one by one, to Will, Nels, Kiliii, and Alex, dropping one off in front of me. Inside is another bag, velvet. We open them at the same time, the others pulling out carved raven and eagle talismans.

As I extract copper tina’as, I begin to understand a little more how she does it all. In her dance with sovereign foods, detailing of lines sculpted to form other than human-kin on metals, and the (re)generation of towns through tourism, Mary makes time for connection with the world around her.

I still don’t know the meaning of the tina’as, and I am not in a hurry to know every detail. For now, each time I pick them up, placing the hooks in each ear, I am reminded of spring days in Sitka, Alaska, soaking in time and the imprints of copper and community.

About Mary:

“I am an Alaskan Native who is passionate about my Tlingit culture. I express myself through making jewelry and art. I find great joy in working in film. When not creating, I am foraging for indigenous plants for cooking and medicine making.

Currently I carve silver, copper and gold. Many of my pieces have spruce root woven into them. I hand-carve, shape and cut all of my materials to create unique pieces, as well as harvesting and preparing the spruce roots that I weave into many of my metal works. Although I may repeat certain designs, each piece of jewelry is one-of-a-kind. My style is Tlingit formline mixed with scroll work. Much of my inspiration comes from local plants. I delight in creating heirloom pieces that are unique to an individual or family.

I have learned most of my jewelry trade from Jennie Wheeler (who is my mother) and from Dave Galanin. Jennie sews with furs and skins and weaves baskets. Dave Galanin is a master carver and jewelry maker.”

See more of Mary’s work here

About the Author:

Deenaalee Hodgdon is an indigenous queer artist and nomad. They circulate seasons between commercial fishing in Bristol bay and participating in various forms of storytelling through the winter. Deenaalee’s writing lies at the cross trails of ethnography, poetry, and frantic free writes. They are happiest when harvesting from the land, living on the water, grounding themselves in the mountains, and learning new practices.