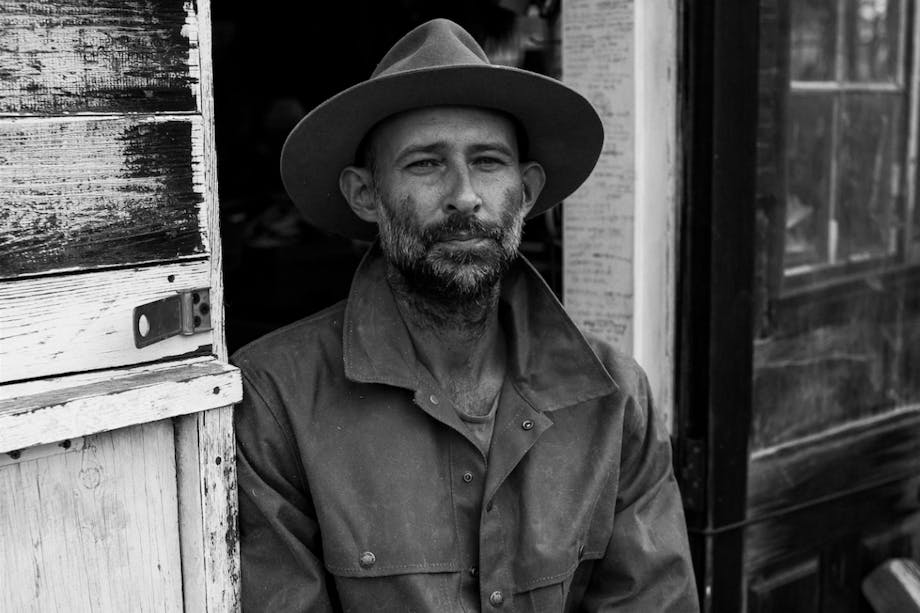

Seattle-based kayak-builder and photographer, Kiliii Yuyan, spends much of his time either paddling the waters of the Pacific Northwest or documenting indigenous communities of the North. His skills are helping to return traditional knowledge of the skin-on-frame kayak and umiaq to the first builders. On the latest Filson Journal story, Kiliii Yuyan of Seawolf Kayak shares with us his journey towards preserving Nanai heritage on the water.

Something bumped my kayak from behind. Bump. More like nudged. Nudge.

I turned around as best as I could in my seat and watched as an orca calf nudged the boat again. Then it rolled into the water and darted under me. I could feel the pressure of the water’s movement through the thin skin of my kayak as it reverberated up my legs.

I paddled forward, parallel to the arid coastline stacked with driftwood logs. As I did, I watched as a large female swam in concert with me, 50 yards away. Off in the distance, several males swam along and followed our trajectory. I couldn’t be sure if this orca calf was leading me someplace as it darted ahead and behind my kayak. It didn’t matter—It was a moment I had lived many times in my imagination as a child. I was paddling inside a story.

I grew up listening to my grandmother’s stories. There was the story of her and the giant fish, and the story of the girl who turned into a swan, and then the story she told once, of the boy who rode the orcas. As a kid, the distinction between reality and myth did not exist. She told me the boy in the story was looking for the Old Man Who Lived Under the Sea. Like Odysseus, he completed a series of challenges on the way. But the part I really remember is the boy riding on an orca, cruising down the river’s mouth into the sea.

My grandmother was Nanai, an indigenous group of people who live along the banks of the Amur river of Russia, living by fishing for salmon. I grew up in the United States, which my parents had emigrated to, divorced from my Native ancestry. But I had the stories, and they woke in me a fierce compulsion to understand the world as my ancestors did. By thirty I had become an expert in so-called ‘primitive skills’, and had built over 40 traditional kayaks.

The kayak is an amazing craft. It’s more than just a boat. When accompanied by the requisite paddling skills, it is a ticket to the most remote destinations. My expedition kayak has hauled a month of gear and endured the battering of house-crushing waves. When I’m in the wilderness, my kayak is my lifeline and partner. Together, we have covered thousands of miles, crept up on bears, and paddled through nights of bioluminescent water.

The boats I build, known as skin-on-frames, use construction techniques that are over 4,000 years old. I ponder this when I’m working on a kayak frame. I pull the cord between my fingers as I wind a lashing tight around two narrow pieces of cedar wood. As I cinch a loop down around the lashing, the cord recesses itself into the wood and vanishes. This is the traditional way to build kayaks, to build them light and strong with minimal waste. When complete, this kayak will weigh just 28 pounds, be stronger than one made of fiberglass, and I’m tying it together. There’s not a metal fastener in the frame, nor any trace of high-tech boat widgets. I don’t need them. When I’m paddling on the ocean I won’t need to worry about batteries or electronics breaking down from saltwater corrosion. Instead, I’ll be thinking about catching a lingcod for dinner and listening to the sounds of oystercatchers winging by.

The elegance of the skinboat reminds me that the genius of its engineering is not by any one person, but generations that have come before. The design evolved from the work of the ancestors of the northern Native peoples—Canadian and Greenlandic Inuit, Alaskan Iñupiat, Russian Chukchi, and more. My own culture, the Nanai built ocean-going boats that were kayaks in form, but constructed differently. They were not made by wrapping skins around frames. It makes me think, “What better way to understand skinboats, and perhaps myself, than go to a community where traditional culture has an unbroken lineage?”

This is how I find myself immersed in the Iñupiat community, out on the sea ice past the northernmost point of Alaska, sitting in a skinboat called an umiaq. The umiaq is the big brother to the kayak. It’s open on the top, about the size of a Boston Whaler, with these particular horns sticking out of the ends. And of course it is covered in sealskins.

Hanging out with Iñupiat hunters, I spend months out on the sea ice, camping in traditional old-school wall tents. I find myself learning about far more than the umiaq. I paddle along the tuvaq, the edge of the ice, chatting and learning about the traditional way that umiaqs are still built here. They tell me about spending all summer chasing the big bearded seals to get the six skins it takes to cover an umiaq. I hear about the skin-sewing marathon, where ladies gather around the umiaq and stitch it up while the skins are damp in just 24 hours.

I’m beginning to understand the essence of this Native culture, and by extension, my own. The traditions, the kayak-building, they bring everyone together. It brings the young people, who eagerly hold pieces of wood together for the adult builders. It brings the elders, who come by to drop a few pieces of crucial advice. By the time an umiaq frame is finished, half the village has spent a day hanging out for some reason or other. I have an American friend who also builds kayaks and likes to say, “If you have clamps, you don’t need friends.” No. If you have friends, you don’t need clamps.

It comes full circle. This autumn, I return to the Arctic, tools in hand, to bring something back to the Iñupiat who have given me so much. History is strange. In Alaska, the kayak vanished a century ago, giving way to skiffs with outboard motors. Somehow, the umiaq survived. I’m bringing the kayak back, by teaching Iñupiat teenagers how to build them in school. We’ll lash those frames together, strong and light. We’ll sew bearded sealskins around them. We’ll bring those kayaks to life just as they did in the old days, before aluminum and gasoline. We’ll take part in the cycle of Native tradition, passing forward our knowledge the way it’s been done since the beginning. In this way, our stories live on.