J. DREW LANHAM: HUNTER-CONSERVATIONIST, POET, AND NATURALIST

I MEET DREW LANHAM AT HIGH NOON IN THE PARKING LOT OF A DEFUNCT HARDEES IN THE TOWN OF NINETY SIX, SOUTH CAROLINA. NINETY SIX IS A RURAL TOWN IN A RURAL STATE, A TOWN MOSTLY KNOWN FOR WHAT IT USED TO BE, FIGURING PROMINENTLY IN BOTH THE ANGLO-CHEROKEE WAR AND THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY. LANHAM PULLS UP IN HIS WHITE SILVERADO AND STEPS OUT TO SHAKE MY HAND. HE’S A BIG MAN, WELL OVER SIX FEET TALL AND BUILT LIKE A BEAR, WITH A WIDE, SINCERE SMILE.

Lanham is an ornithologist, a professor of wildlife ecology at Clemson University, and a poet, naturalist, and hunter-conservationist. A prolific writer, he has authored the award-winning memoir, The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature, as well as Sparrow Envy: Field Guide to Birds and Lesser Beasts. A passionate outdoorsman, Lanham lives his subject matter, fully committed to a life integrated with nature.

Back in the car, we drive down old country roads until the pavement ends. Gravel gives way to red clay as we enter a forest of loblolly pine and mixed hardwood. It’s a warm day in late May and I roll down the window, enjoying the smell of the trees and their relative coolness. Parking at an unmarked turnoff, we hose ourselves with Deet and wade into the dense underbrush.

Lanham swings a machete to clear our path through the thicket and I become aware that he is holding two simultaneous conversations: one with me, and one with every bird, insect, flower, or tree that catches his attention. Occasionally these conversations converge and he announces, “Now you see that? That’s different,” or “Ah. Louisiana Waterthrush! An indicator that water is flowing cleanly.” He readily admits that the problem with going out in the woods with him is “that it takes forever to get anywhere” because something always demands his attention.

“We have to be more than passive watchers of nature ... we use nature everyday. Every breath we take, we’re using what a tree or plant produces. We’re exchanging with those trees, with those plants. If you begin to see that our lives are necessary for nature and nature is necessary for our lives, then you can become a different sort of bird watcher, hunter, photographer, artist.”

This one-hundred-twenty acres of land has been in Lanham’s family since the early 1900s. “My ancestors were here mostly by choice, we think,” he tells me. “This land was theirs after enslavement.” While in graduate school, Lanham’s mother gave him the opportunity to manage the land. “It was sort of a living lab for me,” he recalls, while stopping to admire a beautiful yellow wild flower. “Economic return is important to some degree, to keep things going, but to be on a piece of land and help it recover, I mean that’s everything.” Through timber thinning and the use of controlled burns, Lanham hopes to restore his land and improve deer hunting. “When I climb a tree stand here, it’s different from anywhere else. If I take a deer on land that has my own blood—the blood, sweat, and tears of my ancestors—it simply tastes better.”

“If I go up a deer stand, I might take home venison. I might take home a photo of a bird. Or I might take home a poem"

We walk along an overgrown path, below white oaks and American sweetgum. Tree frogs whistle in the distance and a gentle rain begins to pitter-patter upon the dense canopy above our heads. Lanham mentions that he had heard a yellow-billed cuckoo calling earlier and wondered if it would rain. “My grandmother called them rain crows,” he says. “They’re supposed to predict rain and I guess it did.” Lanham lives on the margins of art, science, and superstition, a niche habitat for the rarest of birds. Partially raised by his deeply superstitious grandmother, whom Lanham called Mamatha, on a farm in Edgefield, South Carolina, Lanham’s formative years were awash in mystical beliefs and portentions from a much older time, something that decades of schooling could not expunge. As a “black birder”—a rarity in the overwhelmingly white avocation, something Lanham calls “the whitest thing you could possibly do”—Lanham advocates for diversity in the outdoors.

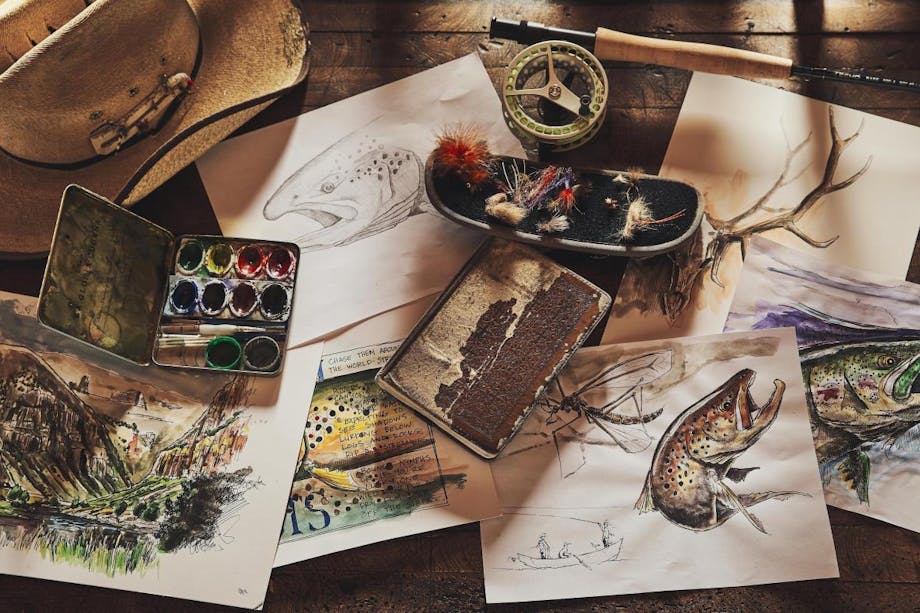

“Difference” is something that Lanham thinks a lot about. His unusual upbringing and the fearless pursuit of his interests has made him a kind of nonconformist, nonspecialized, do-it-all outdoorsman that calls to mind the likes of Aldo Leopold or the archetype of the bygone naturalist. “If I go up a deer stand, I might take home venison. I might take home a photo of a bird. Or I might take home a poem,” he tells me while leaning on his machete. “I do some of my best writing while sitting in the deer stand.”

After a bit more walking, we reach the heart of Lanham’s acreage. A small stream winds its way through the bottom, the earth soft and spongy underfoot. A million hues of green are on display, the understory a riot of ferns. The acoustics of the canopy and water are just right, and we both pause, hushed, to admire the rapturous singing of a wood thrush. There are unusual plant and tree species growing here—a solitary cottonwood, an ironwood, a wild grape vine as thick as my arm—that will surprise anyone who is paying attention. “We have to be more than passive ‘watchers of nature,’” Lanham tells me. “We use nature everyday. Every breath we take, we’re using what a tree or plant produces. We’re exchanging with those trees, with those plants. If you begin to see that our lives are necessary for nature and nature is necessary for our lives, then you can become a different sort of bird watcher, hunter, photographer, artist.”

Reaching down into the soft soil, Lanham digs out a piece of heart pine—what Mamatha, he tells me, would have called “lightwood”—so loaded with pitch that it could be lit by a single match. “I’m a different kind of outdoorsman and I want people to know that it’s okay to be out there being different,” he says looking down at the fragrant pine. “It’s just all about finding joy.”