CIRCA 1983 is Owen Perry, a Canadian interactive designer and photographer by trade. Specializing in landscape and travel photography, Owen wants to create a sense of wonder about the natural world through a unique photographic editing style. His primary influences are the nostalgic qualities of film and Canadian cultural narratives owed to the Group of Seven, National Film Board of Canada (NFB), Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), The Nature of Things, and National Geographic. In the latest Filson Life, join Owen as he hits the road solo through the wild country of Northern British Columbia and the Yukon.

“Even in the mind of the most sophisticated urbanite, Canada is first of all a country of great unfilled spaces, of limitless horizons. Our perceptions emerge from our contact with this space, this thing, this gigantic problem, which is at once the mother of our energies and the source of our anxieties. Canadians are now, by choice as well as economic necessity, increasingly urban people. Yet all of us know that just out there, just beyond the furthest suburb, the country opens up and goes on forever.” ~ Robert Fulford, Canadian author, journalist and essayist (1932–)

The following is Part I of a three post series documenting a trip across Canada this past October. Part I recounts 6 days of travel through Northern British Columbia and Yukon, picking-up in Stewart, British Columbia & Hyder, Alaska, before then heading north to the Yukon and turning back south along the Alaska Highway en route to Prince George.

It’s almost an hour after nightfall and torrential rain when I arrive in Stewart, an isolated coastal inlet town of northern British Columbia’s, Pacific Coast. I had originally anticipated camping at a park outside town prior in the day, but with night fallen and no sign of any let-up in the weather, I decide to find a more reliable shelter than a tent. Where exactly, I’m not yet sure.

Driving through what looks like the town’s main street, the rain and wind give off a threatening howl outside outside the warm confines of my car. Although difficult to see clearly through the windshield, the faint glow of a sign beckons a few hundred meters away and I drive towards it. The sign reads “Ripley Creek Inn.” The main building, looking something reminiscent of a gold rush era saloon, has a faded and chipped-paint exterior. I turn off the main street and down a narrow laneway, park the car, open the door, and then sprint towards what looks like the innkeeper’s office.

After a few rounds of knocking, a light turns on. Through a window, I watch as an elderly man makes his way to unlock and open the door. “Hello, I’m looking for a room for the evening,” I say to him, now thoroughly soaked from the rain. He smiles, nods, and invites me in.

Entering the office it quickly becomes apparent the inn’s scruffy facade hides a quaint ‘Canadiana’ interior, filled with interesting artifacts, photographs and memorabilia from Stewart’s mining days. The man and I engage in a back and forth chat for about ten minutes as he checks me in. He tells me that other than the main building, most of the buildings that comprise the Inn were at one time abandoned, repaired and then relocated from other areas of town. The gentleman then hands me an old, bent brass key, providing me directions to my room.

The room’s rickety old door gives way to another Canadiana style interior. There’s an antique rocking chair in the far corner, and above it hangs a Group of Seven painting. It’s a dreamy winterscape by Franklin Carmichael depicting an early century scene from either Ontario or Quebec. The painting creates warm, nostalgic feelings; thoughts of where I grew up; a place many thousands of miles away.

After charging camera batteries and prepping gear for the next day’s adventure, I fall asleep to the calming pitter-patter of rain on the Inn’s tin roof.

It rains hard throughout the night, but lets-up with the sunrise. Crawling out of bed, I make my way to the window and pull back the curtains to see a light dusting of snow high up on the mountains. It’s the first snow of the season.

It’s a cold, damp and foggy autumn morning — the type the Pacific Northwest is notorious for. Curious to get a lay of the land, I take a walk around town attempting and capture some of this strange and isolated place. I come across a number of charming antiques, including a mining vehicle that looks something like a cross between a vintage Citroën and a tank.

There are many either dilapidated or abandoned buildings around town. The most notable of these is the Empress Hotel, a large wood-framed structure built in 1908 by a German financier for the Canadian Northeastern Railway. A sign posted in front says it’s for sale, though judging from the exterior I imagine the restoration could be quite costly.

After buying some weak coffee and chatting with a few friendly locals at the town’s only cafe, I embark on the day’s destination – the Salmon Glacier. The journey, which begins at the Alaska border in neighbouring Hyder, follows an old mining road to a lookout about 20km up the Salmon River Basin.

As I’ve come to understand it, the backstory on Hyder and Stewart is one of boom and bust. Both towns, one American, the other Canadian, were part of a 1920’s gold and silver rush that employed over 10,000 people at its peak. From 1920 until it’s closure in 1952 the Canadian-owned Premier Mine was actually the largest gold mine in North America. Time and the mining industry haven’t boded well for either town however, and today less than 500 people live in Stewart, and a little under 90 in Hyder.

As in neighbouring Stewart, many of the homes in Hyder look rather derelict, though still manage to maintain a certain charming quality. The post office, one of the only remaining government institutions left in town, still operates, delivering mail by air once every week.

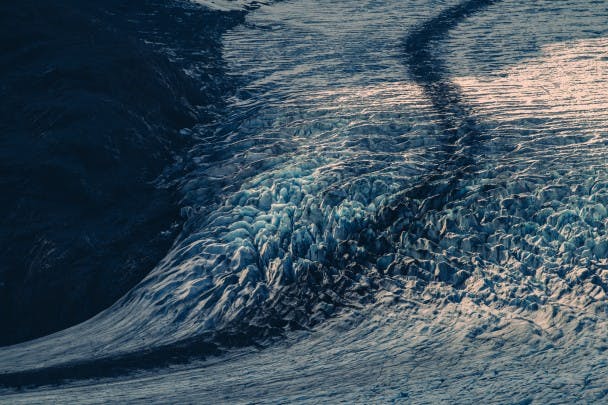

While no longer supporting a booming mining industry, the Hyder and the Salmon River Basin does offer stunning natural beauty, most notable of which is the Salmon Glacier, the 5th largest glacier in Canada.

Driving up toward the lookout you catch your first glimpse of the glacier’s toe. It snakes down in a distinct ’S’ pattern to meet with the river of the same name. I stop to take a photo, but make it quick, as multiple signs caution rockslides. Later on I come across a few large boulders that have fallen from the surrounding slopes and onto the road… so apparently they’re not kidding.

I arrive at the lookout in a blizzard, the glacier shrouded in a snowy fog that seems to waver between thick and thicker. One might wonder if early October is the best time to visit a place at such altitude and prone to long periods of sun unseen.

Photography, and especially landscape photography as I’ve come to understand it, can involve a certain degree of patience. With the camera set, I wait…and wait… Ready to capture the glacier as soon as, or perhaps if, the storm and clouds taper off.

While waiting on the weather, I make use of time exploring the area around the lookout and come upon a beautiful flock of White-tailed Ptarmigan. They’re startled yet inquisitive – as if perhaps I were the first human they’ve ever seen.

Almost three hours after arriving, the storm subsides and the midday sun begins to poke through the clouds every so slowly, revealing the glacier in entirety. It’s simply enormous, beginning from beyond the horizon and descending to the base of cliffs hundreds of feet below the lookout. The view leaves one feeling small and truly humbled; your tiny bit of existence bearing down like the weight of a mountain.

While a wider view of the Salmon Glacier is an engrossing visual experience, closer inspection with a telephoto lens reveals incredible textures in the ice.

It’s about 4pm when I begin the drive back down, the afternoon sun radiating beautiful beams of light through the clouds and between mountains. The further down I drive, the more the Salmon River is revealed in the valley below.

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Salmon River and Portland Canal were the hunting and fishing grounds of the Nass Indians. The Nass River Indians knew the head of the Portland Canal as Skam-A-Kounst, meaning safe place. It is said that the canal and area were used to retreat from the harassment of the coastal Hiadas, a tribe recognized as one of the more aggressive and intelligent along British Columbia’s coast and primarily based in the Queen Charlotte Islands – the archipelago now called Haida Gwaii.

The next day I take some advice from a local and try my hand fly fishing for steelhead on the Meziadin River. From a fishing perspective it’s an ill-fated effort, as I spend most of my time fighting frigid temperatures and fast-moving water while roll casting from muddy, tree-lined river banks. From a photography perspective however, I’m happy to capture atmospheric shots of cliffs and glaciers heading back to Stewart.

The second part of the journey begins the following morning, as I depart Stewart on a 3-day 1500km trip north to the Yukon, and eventually back south to Prince George via the Alaska Highway. It’s raining when I leave, but as I drive north on the Stewart-Cassiar HWY it gradually turns to snow. While still early October, the further north I go the more the first signs of winter become present. The contrast between autumn leaves and snow-covered mountains is painterly.

A few hours into the day, I stop at Kinanskan Lake Provincial Park for short rest. Walking to the end of a snow-covered dock, I look down. The water is crystal-clear. There are sizeable rock formations on the lake bottom, and what seems like a drop-off and possible fishing hole. Fetching a casting rod from the car, I briefly try my hand at perhaps catching dinner. Luck is on my side, as I land a hard-fighting, pan-sized rainbow with a spoon on about my 5th cast. I gut and clean the fish on the dock, pack it away in some snow, then get back on the road.

With a proclivity to stop and take photos and/or fish at every picturesque lake or river along the way, my progress on the day is slow. I remind myself that trip isn’t a race; that the journey and experience are far more important than the destination or time of arrival.

About a hundred kilometers from the Yukon border and with nightfall approaching, I pull into Boya Lake Provincial Park and set-up camp. That evening I cook the day’s catch over the fire in butter and lemon, and then share it with some neighbouring campers — two gentleman headed back from a summer of whitewater rafting in Alaska. We all agree that it’s delicious – perhaps the best fish we’ve ever tasted. The two men return the gesture with some cheap whiskey, as we share stories about our past adventures and future endeavours before turning into bed sometime after 9pm.

When I awake, there’s a brilliant sunrise over Boya Lake. The water, which looked black when I arrived the evening prior, now glows a brilliant emerald green as the sun paints gorgeous hues of pink and purple on the clouds and surrounding mountains.

After a few casts, I pack the car and return to the road around 8am, reaching Watson Lake, Yukon, around 9:30. Breakfast is at Kathy’s Kitchen, which seems to be the only breakfast place open in the small town. I order the special, which for $12.99 comes with three pancakes, three sausages, home-cooked hash browns, and of course, weak coffee.

Before departing town, I stop to wander The Sign Post Forest, an impressive expanse of license plates and signage brought from all over the world by pilgrims of the Alaska Highway. It’s a testament to symbolic meaning of the highway for travellers; it’s frontier narrative; an escape from modern society; the beginning of a new life; the ‘I (we), finally did it!’ moment.

From Watson Lake I drive east on the Alaska Highway, which eventually cuts south back into Northern British Columbia. There are signs warning for buffaloes on road, and I soon come upon a number of large herds that graze quietly on the roadside greenery. I would later learn that British Columbia’s wild buffalo herds, though small, are currently thriving in this quiet corner of the province.

Around midday, I stop at the Liard Hot Springs for a quick swim. It’s therapeutic, mineral-rich waters sooth my road-wearied body.

After the dip, I continue south into Stone Mountain Provincial Park. Part of the Northern Rocky Mountains, Stone Mountain boasts beautiful snow-dusted peaks as well as a brilliant display of fall colour.

Just beyond the park boundary, a large elk gallops across the road and up an adjacent hill. Scrambling for my camera, I manage to snap a photo before he dips back into the forest and out of sight.

I pull into Tetsa River Regional Park around sunset with just enough time to explore and cast a few flies before the sun dips below the treeline. There are a few nibbles, but nothing seems to be taking the fly.

Later that evening I run into Bob, the park’s caretaker. Asking about the fishing, he’s happy to help. He insists there are trophy-sized bull trout in the Tetsa – holding his hands out wide and then boasting about how he’s seen many of them over the past few weeks. The news gives me great excitement. He then tells me where to go — a deep pool about a km down the river from the campground. He also takes a quick look through my fly box, pointing-out the right pattern for the job. Bob’s advice would prove that there’s nothing like local knowledge when it comes to fishing an unknown river.

Every bit of stoicism I can muster is required to exit the warm confines of my sleeping bag the next morning. It’s below freezing and a thin layer of frost coats the inside of the tent. I slip into a pair of frozen boots, gather my gear, and begin the trek down to the river, trying not to think about the numbness in my hands and feet.

Twenty minutes later I arrive at the pool in the river Bob had referred to. The sun is now up and shining brilliantly on the bubbling river.

Standing above the pool, I cast across across to the opposing bank and allow the fly to swing with current. I feel a few tugs, but like yesterday the fish doesn’t seem to want to take the fly. By the third cast, water has frozen and almost completely surrounded the eyelets of the rod. I clear it off with numb fingers and cast out once more across the river, allowing the fly to again swing into the deepest area of the pool. I feel a strong tug this time and pull the line to set the hook. Finally, a fish on!

The Bull Trout seems almost as surprised as I am, or perhaps as cold and numb as I am, and doesn’t put-up the most heroic of fights, taking line only once before flipping and flopping in the shallows as I bend over to land it. The fish has brilliant green and purple toned skin that glistens with the morning sunlight. I take a few photos before releasing the fish back into the Tetsa.

After fishing for another hour without further luck, I decide to make my way back to camp. I suppose catching a trophy-sized bull trout from the Tetsa will have to wait until next time. Before leaving, I make sure to thank Bob for the fishing tips and let him know I’ll be back someday soon.

Around 10am I’m back on the Alaska Highway. Making a stop at a gas station in Fort Nelson, I fill up on fuel and buy some weak coffee before continuing the 900 km drive south back to Prince George.

About 300km outside of Prince George I pass through the picturesque, but soon to be dammed, Peace River Valley. I stop at a lookout to take a photograph of a landscape that will change immensely over the next few years. A recently approved $8.8 billion hydro project will flood over 20% of the fertile farmland in the valley, threatening large swaths of wetlands and wildlife habitats in the process. While the government presents it as a “Clean Energy Project,” the actual reason for the dam is to supply energy to new natural gas fracking developments in British Columbia’s northeast, which in-turn will power the extraction of oil from Alberta’s tar sands.

It’s a beautiful scene dyed by somber thoughts. Maybe a fitting conclusion to the first part of a journey through today’s Canada; a country of immense natural wealth and beauty, but set on a path of development that may ruin many of the pristine lakes, rivers, forests and wildlife habitats that make it such an amazing place to explore.