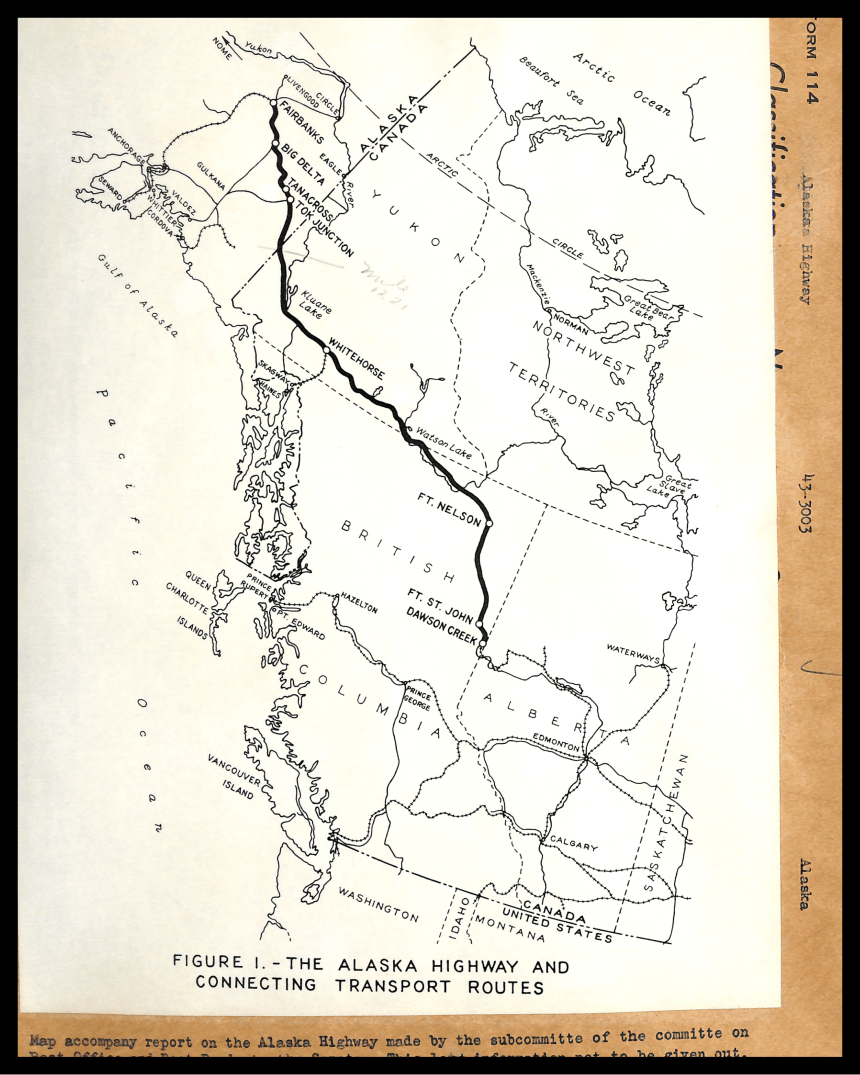

Seventy-eight years ago, the Army Corps of Engineers completed one of its most ambitious assignments of World War II—the Alaska-Canadian (Alcan) Highway. After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the Alcan Highway became a high priority. Eight engineer regiments were assigned: 18th, 35th, 340th, and 341st, and Black 93rd, 95th, 97th, and 388th reluctantly added.

Race relations in American were very different in 1942, which was still in the era of Jim Crow and a segregated Army. Opportunities for Blacks were rare, and expectations low. They were unwanted for duty in the front lines and often treated with condescension or contempt by their White leaders and other White soldiers.

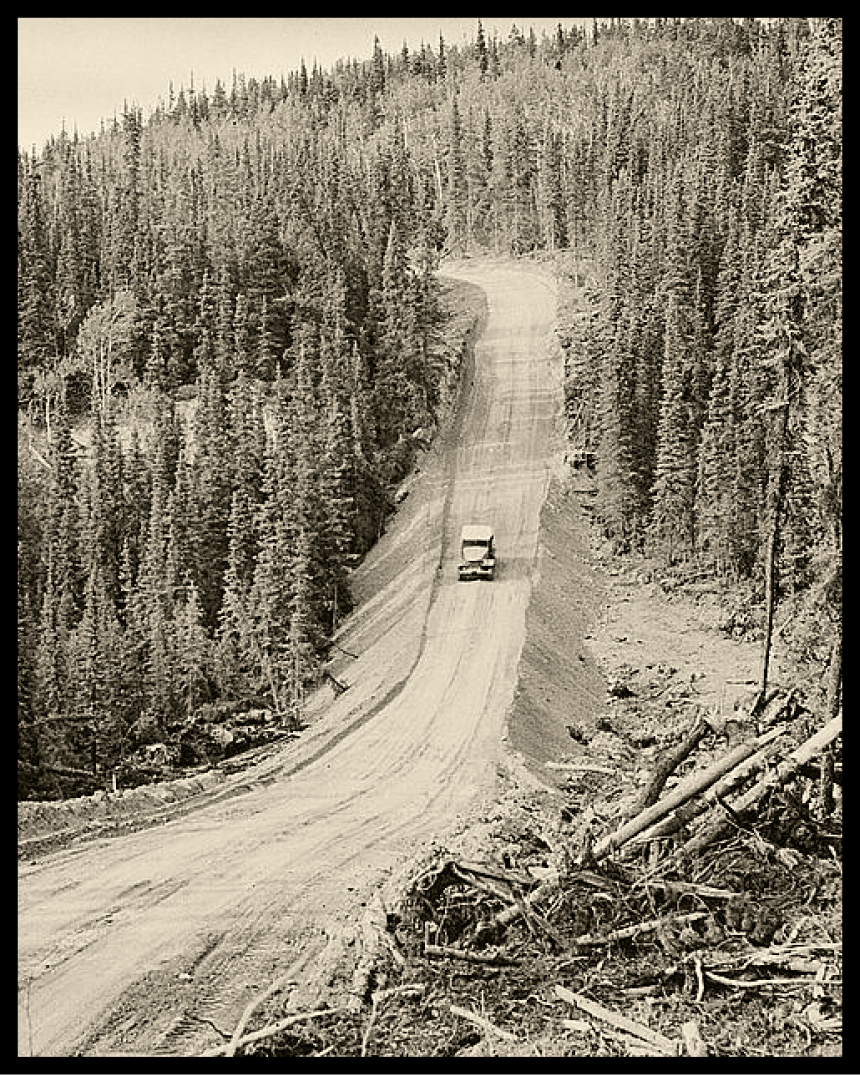

Faced with countless odds, they persevered and accomplished what no others could do—build a highway in record time through insurmountable and rugged terrain. Once built, the road became the only route linked to the north for plane refueling and supply routes.

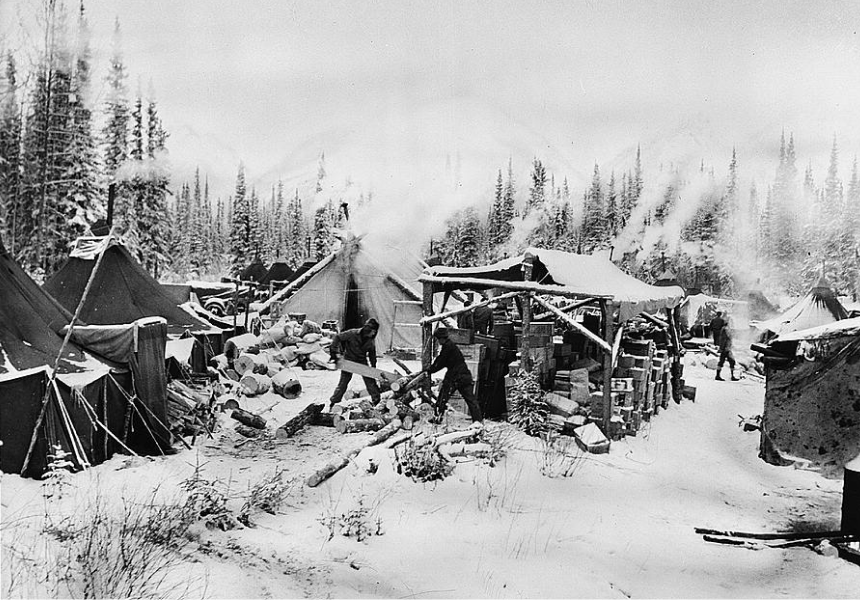

The Black regiments—many of whom knew only Southern weather—overcame adverse conditions and harsh climate with insufficient clothing and accommodations. Many top Army personnel feared the Black regiments. Jim Crow Laws were followed in the Army, which enforced discriminatory policies of segregation and isolation. As a result, the Black regiments’ camps were built in isolated areas away from towns and had cloth tents as living quarters, while the White soldiers were housed in Quonset huts under much better conditions.

One of the first camps along the Alcan Highway route to be set up in the northern regions of Alaska on 01/01/1942. A sawmill supplies building materials and wood for fires. Source: Library of Congress

The crowning achievement of the 93rd was the 70-mile road from Carcross to the Teslin River. On June 16, 1942, the bulldozers cut through the woods to Johnson’s Crossing, completing the road to Teslin River in just 1.5 months. To accomplish this, the 93rd had to build or rebuild bridges, install culverts, and grade and widen the existing road.

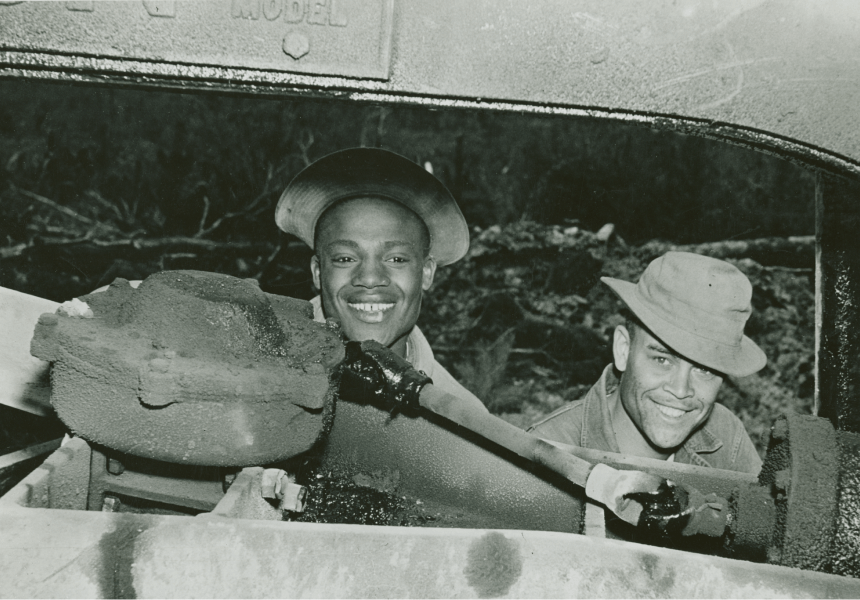

They accomplished all of this with hand tools, picks, shovels, axes, and hand saws. They operated bulldozers and drove trucks while struggling through muskeg, mud, mosquitoes, gnats, food shortages, and broken bones. From June 5, 1942, to October 1, 1942, the 93rd built 240 miles of road, including upgraded roads, new culverts, and four new bridges.

The 95th was the best trained of the four Black regiments. It was the first to learn how to drive Caterpillar bulldozers at the Engineer Replacement Center (ERTC) at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. They were also the most educated regiment, consisting of high school and university graduates mostly from Baltimore and Washington.

At Sikanni Chief River, the 95th was challenged to build a bridge in five days. The regiment bet their paychecks they could get it done in four. At noon on Friday, June 24, 1942, the bridge was completed—in just three days. The bridge was tested, and a large keg of beer and liquor was provided to celebrate the amazing feat.

The 95th was the best trained of the four Black regiments. It was the first to learn how to drive Caterpillar bulldozers at the Engineer Replacement Center (ERTC) at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. They were also the most educated regiment, consisting of high school and university graduates mostly from Baltimore and Washington.

At Sikanni Chief River, the 95th was challenged to build a bridge in five days. The regiment bet their paychecks they could get it done in four. At noon on Friday, June 24, 1942, the bridge was completed—in just three days. The bridge was tested, and a large keg of beer and liquor was provided to celebrate the amazing feat.

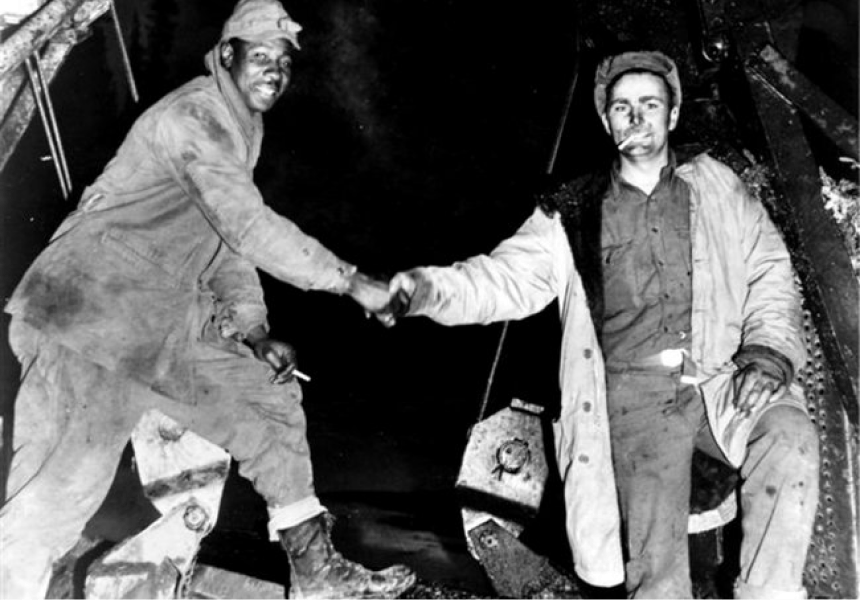

The Black soldiers of the 97th regiment met up with the White soldiers of the 18th, connecting the two segments, on October 25, 1942. William E. Griggs, the official photographer of the 97th, took more than 1,000 photos of construction on the highway. The two regiments met head-on in the forests near Beaver Creek, by milepost 590 in the Yukon Territory. Corporal Refines Sims Jr., a Black engineer from Philadelphia, was driving the bulldozer south when he saw trees start to topple over on him. He slammed his vehicle into reverse and backed out just as another bulldozer, driven by Private Alfred Jalufka of Kennedy, Texas, of the 18th regiment, broke through the line.

The men moved to a nearby creek where the light was better. They looked at each other, grabbed hands as they were standing on their machines, then gazed at cameraman Harold W. Richardson, an editor of the Engineering News-Record of Chicago who captured the historic moment. Sims and Jalufka became icons in the Alcan Highway’s history. The 230 miles through mountains and muskeg was completed.

The 388th Battalion was formed from the 93rd regiment. They are the least recognized and publicized battalion. On January 10, 1942, the 388th began training for five months in Louisiana at Camp Claiborne, after which it was assigned to the Canol Pipeline Project. The battalion arrived in the first two weeks of June 1942.

The battalion’s first assignment was to build living quarters, unload supplies arriving from Edmonton, and cut firewood for steamboats. The engineers lived in pup tents. Most of their time was spent on 550 miles of pipe that had to be handled by hand. That meant the battalion’s members were posted along the route from Alberta to Norman Wells, Canada.

On June 28, 1942, Lieutenant Willis G. Gardener, commander of the 388th, slipped on a wet board and fell into the Clearwater River. Realizing he was struggling and about to drown, two of his men, Sargent Robert Hayes and Technician Hubert Massie, jumped into the water with their clothes and heavy shoes.

Despite the strong current, they managed to get Gardener to the side, saving his life. For their bravery in saving him, they were awarded the Soldier’s Medal by Brigadier General Ludson Worsham, which was presented at a ceremony in Fort Smith during which the men had their photograph taken with the general. They remained in the Yukon to build the Canol Road from the highway to Normal Wells, Canada.

Of the estimated 11,000 troops who were assigned to Alaska, 3,695 of them were Black. Few were recognized or acknowledged in books, newspapers, or mainstream media. Often, they were simply overlooked.

In the end, the 1,700-mile highway from Dawson Creek, Canada, to Delta Junction, Alaska, was completed in 8 months and 12 days. The Black regiments that built the Alaska Highway established a reputation for excellence, especially in bridge building. Largely ignored for over seventy years, they finally received proper recognition for their achievements and that is still not enough. Nonetheless, they were steadfast heroes in the land of the midnight sun.

Black soldiers building a culvert along the Alcan Highway. Source: Turner G. Timberlake Photo Collection