For more than 50 years, LWCF has been called America’s most important tool in conservation. But all that was subject to change last September when authorization for the fund faced the legislative chopping block.

What is LWCF?

In the early 1960’s, heightened awareness regarding the depletion of natural resources and the increasing need for public recreation areas brought about the creation of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act. The idea was relatively simple; use revenues from the depletion of offshore oil and gas to protect and conserve America’s land and water resources. Each year, offshore oil and gas companies operating on the Outer Continental Shelf pay royalties into the fund – and it’s no insignificant amount – each year the royalties amount to around $900 million. Another bonus, the fund comes at no cost to taxpayers, funded exclusively by oil and gas royalties.

The fund was initially created to protect and preserve national parks, national forests, wetlands, wildlife refuges and waterways, but has since widened it’s reach to include funding for everything from state parks to ballparks and nearly everything in between. Money from the fund has protected millions of acres across the country, in every state, and nearly every county in the United States. Funding from the LWCF provides the sturdy backbone for federal land acquisition for the U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Bureau of Land Management.

Places like Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona, Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado, and Antietam National Battlefield in Maryland have all received significant funding from the LWCF – just to name a few. And, in Montana alone, the LWCF has helped establish and secure more than 70% of the states’ fishing access sites.

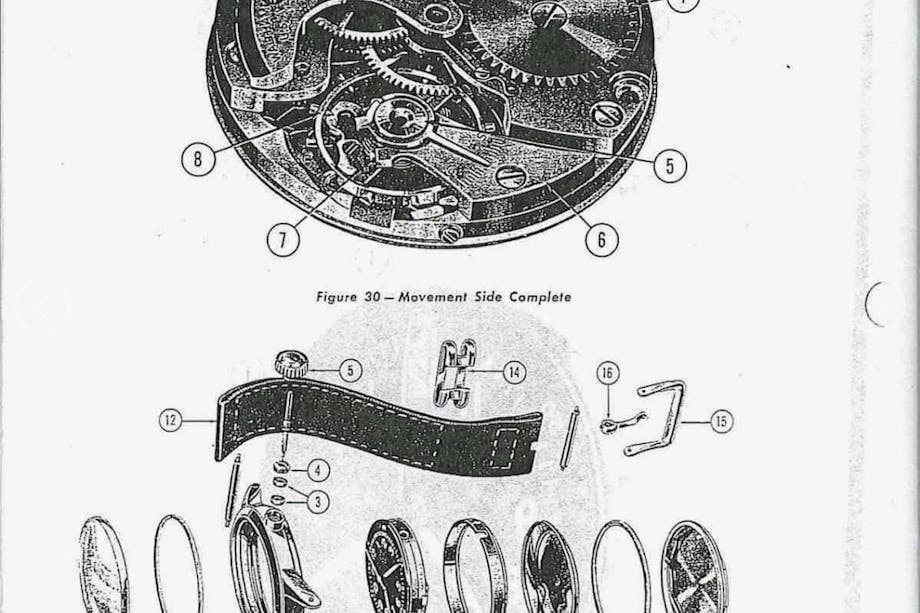

Art by Ed Anderson

The History of LWCF

In 1964, Congress officially authorized the Land and Water Conservation Fund. The fund was initially authorized for a twenty five year period, then reauthorized in 1990 for another twenty five years. The fund expired again in September 2015, but was extended three years while legislators determined the fate of the fund.

In February 2019, Senators Maria Cantwell, D-Washington, and Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska introduced the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management and Recreation Act (S.47). The bill is named after John Dingell, Jr., who passed away in February, 2019, and holds the record for the longest serving member of Congress in American history. Dingell was a staunch conservationist and played part in passing both the Endangered Species Act (1973), and the Clean Air Act (1990). He represented the state of Michigan for more than 59 years.

Among a host of other conservation and public land based legislation, the bill included the permanent reauthorization of the LWCF. Shortly after introduction, the bill passed both the Senate and the House with incredible support from both political parties. On March 12th of this year, President Trump signed the bill into law – a huge win for conservationists, backpackers, hunters and absolutely everyone who enjoys time well-spent outdoors. The permanent reauthorization of the LWCF is undoubtedly one of the great conservation victories of recent history, and it’s hard to overstate exactly how critical this will be for public land, public access and public recreation in the coming years.

What’s Next for LWCF?

Though the LWCF receives $900 million per year in oil and gas royalties, not all – or even a majority – of that money is appropriated for use on Land and Water Conservation Fund projects. Since 1965, only a fraction of the fund annually has been considered mandatory for spending on LWCF specific projects, and only once in the history of the fund has the full amount been appropriated by Congress for LWCF use.

Of the $40 billion in funding available to the LWCF since its inception, only $18 billion has gone to fund LWCF projects. The remainder of the fund is reserved for discretionary spending by Congress, meaning that money can be used for an array of purposes not pertaining to protecting and conserving the nations natural resources.

Once in 2017, and again 2018, the Obama Administration tried to fully authorize the fund, calling for $900 million in mandatory allocation. Both times the effort was thwarted by opponents to full authorization. Supporters for increased funding cite numerous unfunded conservation and public lands projects and improvements; opponents believe the funding is being best used elsewhere.

While the permanent reauthorization of the LWCF has been a great victory for outdoors-folks across the nation, the full or increased partial authorization of the fund will certainly be a cause that requires support moving forward. With increased funding, the LWCF can increase its’ reach and support, creating new opportunities on public land, and protecting existing ones for generations to come.