WILDFIRES ACROSS THE U.S. have become increasingly large and uncharacteristically extreme, due to factors including climate change and unhealthy forests. This puts communities, habitat, and watersheds at risk. It also means that the women and men who work on the front lines to combat wildfires are facing more dangerous conditions.

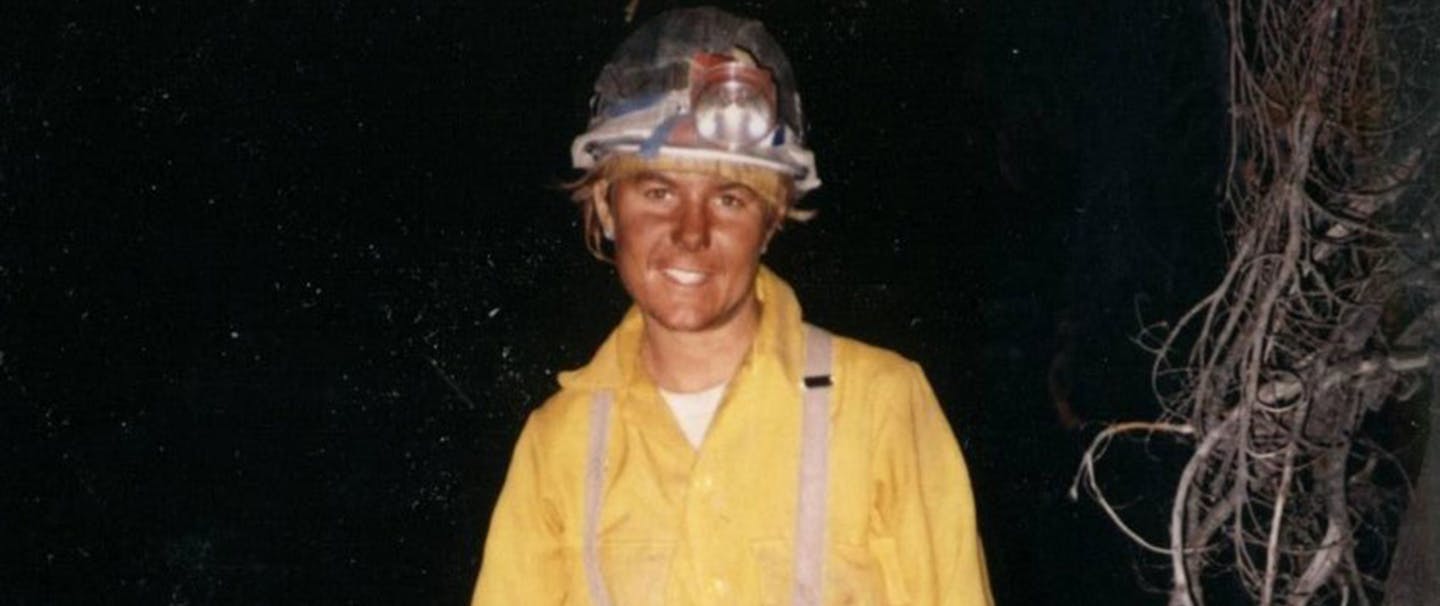

Who are the people who undertake this arduous, smoky, dirty, relentlessly hot, and risky mission to protect our forests and grasslands and the residents and property in adjacent communities? And how do they go about containing and suppressing a raging wild fire?

Most fire personnel are employed by local, state or federal land management agencies. The U.S. Forest Service, which plays a primary role in funding and staffing wildland fire containment efforts across the nation annually employs about 10,000 full-time and seasonal wildland firefighters.

Wildland firefighters differ in gender, size, age and background, but they all have a minimum level of training and fitness in common. Virtually everyone who officially approaches a wildfire is required to be red-carded (having passed the minimum training module for wildland firefighting) and be able to pass some version of the work capacity test, with the most difficult level requiring “rucking” a 45-pound pack for 3 miles in 45 minutes or less.

ENGINE CREWS

How wildland firefighters fight a fire depends on the type of crew to which they’re assigned. Members of engine crews work on specialized fire engines of varying sizes that are equipped to deliver water and foam to a wildfire. The crews suppress or help contain a fire primarily through the application of water. They are able to set up portable pumps from a water source, be it a stream or a tank, and “lay” hose out for ground crews to use while fighting a fire or “mopping up” (making sure fire and hot spots are out following containment).

HANDCREWS & HOTSHOTS

Handcrews are the infantry of firefighters, typically 20 person teams, who construct handline, hold containment lines around the perimeter of a fire, and conduct mop-up operations. Handlines are built with hand tools (versus line cleared by a bulldozer) by clearing vegetation down to mineral soil to create a fuel break that can slow or stop the advance of a fire. The crew is led by both a sawyer, who uses a chainsaw to clear a path of vegetation, and his swamper, who scouts the line, and helps clear sawed vegetation and pack saw fuel and gear. Other firefighters dig line behind them, with shovels or specialized firefighting hand tools, like pulaskis and hoes.

Interagency Hotshot Crews (hotshots) are the most elite type of handcrew. Hotshot crews are collectively required to have extensive experience and training, and each member must maintain a high level of physical fitness. They are often tasked with the most demanding and treacherous assignments and frequently respond to large, high-priority fires. They can be required to hike long distances to remote locations, while toting their tools and 45-pound packs.

Hotshots are trained and conditioned to rapidly build line in steep and treacherous terrain, building it faster than most people can hike. They are also highly skilled in burnout operations, which involves setting fire to unburned fuels located between the control line and main fire to strengthen the line in attempt to stop a fire’s advance.

AERIAL ATTACK

Smokejumpers and rappellers are principally initial attack firefighters, and are specialized to reach wildfires shortly after they are spotted. After parachuting from a plane or rappelling from a helicopter to the safest, most proximate location to the fire, these firefighters work in teams of two to twenty. Using hand tools to control or extinguish the blaze, these crews are prepared to be self-sufficient with minimal gear and supplies for up to 48 hours. They can provide a ground assessment and order additional resources to best control the fire, like water and retardant drops or additional crews to take over an extended effort.

One of the toughest parts of being a smokejumper or rappeller occurs after they complete their duties on the fire. They have to be prepared for heavy “pack-outs”, because while they get to a fire by air, many times they have to hike to the nearest road for pick up. This requires being able to carry 100-plus-pounds of gear cross country, sometimes over miles of steep, rough terrain.

SAFETY FIRST

Along with a commitment to helping protect lives, property, and our shared public lands, wildland firefighters share a commitment to safety. Regardless of how they arrive to a fire or what tools they use to fight it, safety is the top priority of person fighting a wildfire. Every good crew member is constantly assessing principals and standards relating to escape routes, safety zones, communication, hazard lookouts and other concerns. While the job is inherently perilous and increasingly dangerous due to hotter and drier conditions, firefighters are steadfast in doing their jobs in the safest possible way, for themselves and for the protection of their brothers and sisters on the fireline.