THE CHANCES ARE THAT WHEN WALTER HARPER AWOKE ON OCTOBER 25, 1918, IN HIS BERTH UPON THE SS PRINCESS SOPHIA, HE FELT CONFIDENT THAT EVERYTHING WOULD BE OK. GRANTED, THE SHIP HAD RUN AGROUND THE PREVIOUS DAY ON VANDERBILT REEF JUST OUTSIDE JUNEAU, ALASKA, WHILE HEADING TOWARDS VANCOUVER, CANADA. BUT THE DOUBLE-HULLED VESSEL SEEMED TO BE DOING FINE, AND THE CAPTAIN HAD ORDERED NO EVACUATION. HE HAD BEEN IN MUCH HAIRIER SITUATIONS BEFORE AND CAME OUT FINE.

But not much later, a fierce winter storm roared in from the pacific ocean, shoving the ship off the rocks and sending it under the waves. Harper, his new bride Frances, and 362 other souls perished that day; there were no survivors. It was a tragic end to an extraordinary life.

“Twenty-one years old and six feet tall, he took gleefully to high mountaineering, while his kindliness and invincible amiability endeared him to every member of the party”

Five years earlier, on June 7, 1913, Harper had strode to the top of Denali, known then as Mt McKinley. After three months of laboring up its slopes, he became the first human to stand atop the highest point in North America. He was only twenty-years-old yet already an impressive outdoorsman.

When Harper was only two-years-old his father, an Irish gold prospector Arthur Harper left home never to return. His mother, Seentaána, a Koyukon-Athabascan indigenous person, raised him on her own. Growing up in his home village of Tanana, deep in the Alaskan interior on the Yukon River not far from the Arctic Circle, he spent his days learning how to survive off the land. Fishing, hunting, tracking, and dog sledding were second nature to him.

When he was sixteen-years-old, a moment occurred that forever altered the trajectory of his life. That was when Archdeacon Hudson Stuck arrived in his village during one of his trips through the state. An Episcopal missionary, his long-distance circuits would cover thousands of miles during all types of weather. Even though Harper spoke little English and had little formal schooling, Stuck was impressed by the young man and convinced his mother to send him to his missionary school in nearby Nenana.

It wasn’t long until he spoke fluent English and started accompanying Stuck on his journeys throughout the state. He would work as his interpreter, riverboat pilot, and winter trail guide while continuing his education. Affable and easygoing with natural charisma, he teamed well with Stuck, who became a surrogate father figure to him. The two men were inseparable for the next three years.

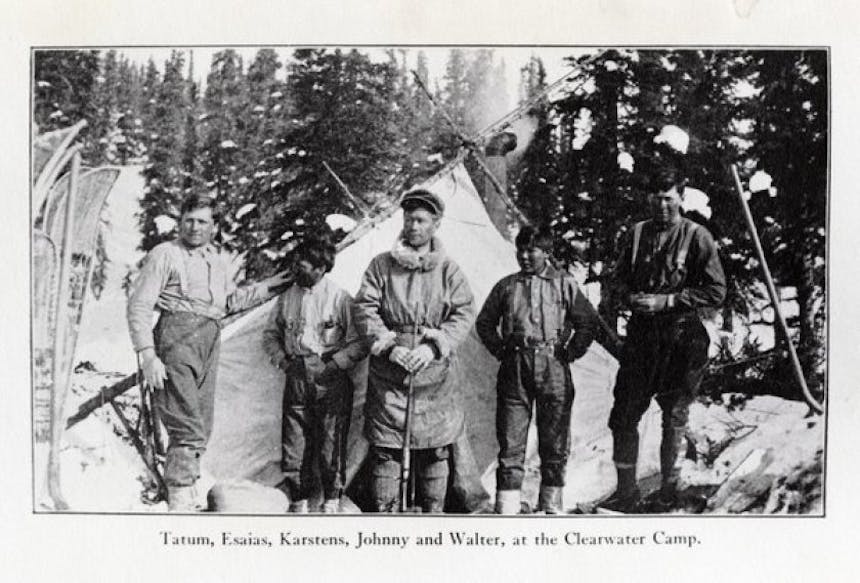

A lifelong amateur mountaineer, Stuck had long harbored a desire to climb the massive mountain that rose towards the sky. In 1913 he recruited Harry Karstens (who would later become the first superintendent of Denali National Park) to be his co-expedition leader. Also joining them would be a young mountain climber and Episcopal priest Robert Tatum. The last member of the team would be Harper; someone Stuck knew would be a perfect fit. “Twenty-one years old and six feet tall, he took gleefully to high mountaineering, while his kindliness and invincible amiability endeared him to every member of the party.” wrote Stuck afterward. It was an addition that would save the team time and time again.

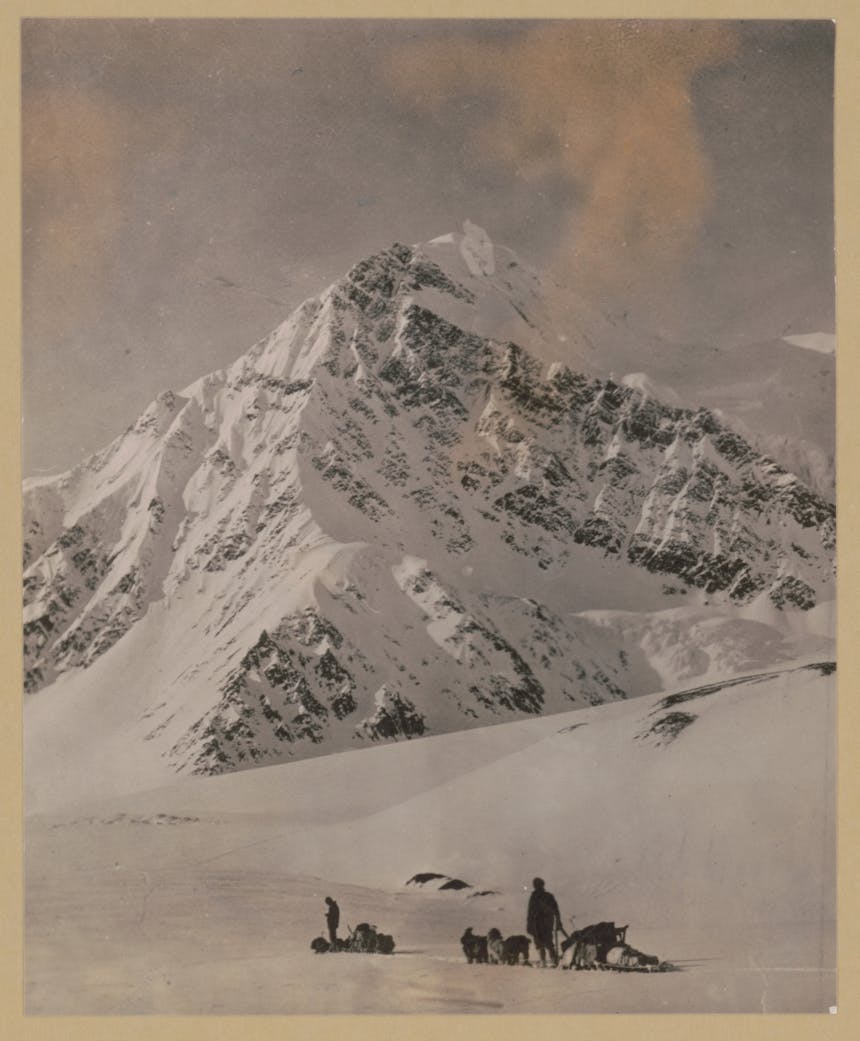

Unlike today, when climbers can just hop a flight to basecamp to climb the mountain, back then, just getting to the beginning of the climb was laborious. A ton and a half of supplies were ferried to the base of the mountain by dog sled from over fifty miles away. Once basecamp was established, they spent weeks transporting supplies ever higher. Denali has the highest vertical rise on the planet, rising almost three and a half miles straight up to 20,310 feet.

By the time they had made it halfway up the mountain six-weeks later, after trudging up glaciated slopes, disaster struck. An errant match caused a considerable cache of supplies to burn up. Undeterred, they fashioned new tents from scraps, adjusted to what they had left, and continued climbing higher. Through it all, Harper helped keep spirits up.

A TON AND A HALF OF SUPPLIES WERE FERRIED TO THE BASE OF THE MOUNTAIN BY DOG SLED FROM OVER FIFTY MILES AWAY. ONCE BASECAMP WAS ESTABLISHED, THEY SPENT WEEKS TRANSPORTING SUPPLIES EVER HIGHER

The next roadblock was not far out. An earthquake had occurred the year before, causing a massive icefall to cover an easy route used the year before by another expedition. Instead of a simple three-day hike, Karstens and Harper spent three weeks hacking out stairs through jumbled blocks of ice and snow-filled slopes. Karstens later described Harper as fearless and said they would have failed without the young man’s endless vigor.

By the time they established their final high-altitude camp at 17,500 feet both Stuck, and Tatum were struggling. The archdeacon, in particular, was in trouble. A forty-nine-year-old lifelong smoker, each breath was a struggle, and he would periodically blackout. But the team decided to try for the summit. The decision to put Harper in the lead was a simple one. “Karstens recognized that any chance they had to succeed hinged on having their strongest climber lead, and that was Walter,” says Mary Ehrlander the author of Walter Harper, Alaska Native Son. “So, he took the point and powered them to the top. At the end of the climb, he literally had to pull Stuck to the top.”

"Karstens recognized that any chance they had to succeed hinged on having their strongest climber lead, and that was Walter...So, he took the point and powered them to the top. At the end of the climb, he literally had to pull Stuck to the top."

After they made it back to civilization and told of their successful endeavor, Harper was celebrated for a little while but soon faded into the background. Karstens and Stuck came to the forefront. Encouraged by his, he continued his education. He went to school for three years in Massachusetts and another two years back in Alaska.

In 1917 he met his wife in Alaska, and Stuck married the two of them in his hometown of Ft Yukon. He decided to become a medical missionary to better the lives of his native Alaskans and follow in his mentor’s footsteps. After spending their honeymoon hunting for game to keep Stuck’s mission stocked in food for the winter, the two caught the last ship heading south before winter to take him to Philadelphia for school. Two days after departing Skagway, Alaska, to embark upon his next adventure. He never made it. Who knows what he might have accomplished next.