Started on September 1, 1911 and completed in 1916, the Hiram Chittenden Locks, alternatively called Seattle’s “Big Ditch,” or “Ballard Locks,” as they are commonly referred to today, helped make possible a new era in maritime commerce and shipping business for Salmon Bay, Lake Washington and all points in between.

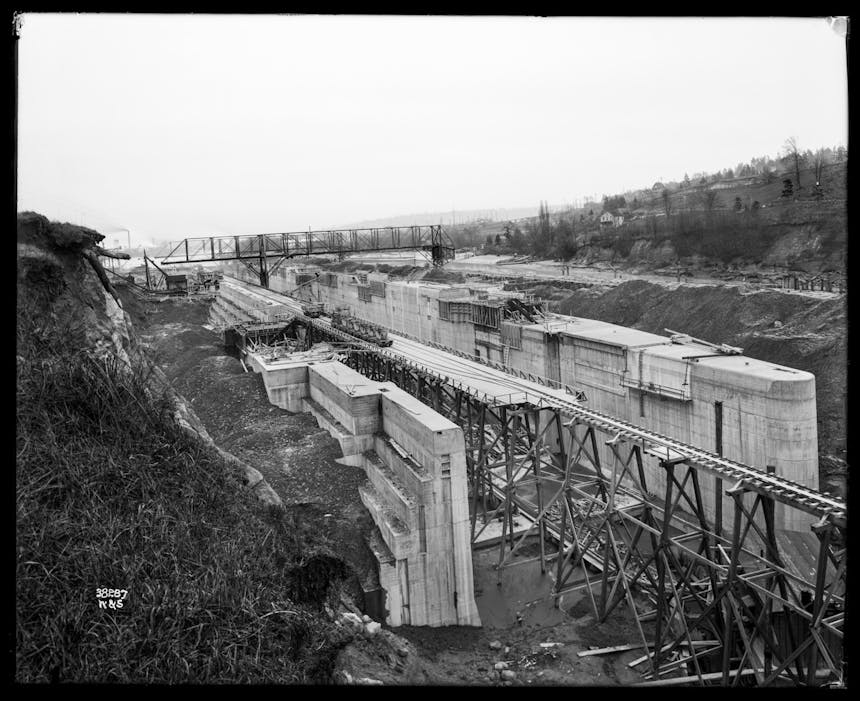

Looking out on the locks today, it is easy to forget that at one point in Seattle’s history, there was no major waterway connection from Puget Sound to the interior past Lake Union. It’s also easy to forget that not everyone was thrilled with the prospect of a new canal: shipbuilders, shingle mill owners, lumberyards and others lining Salmon Bay experienced a water level rise as a result of the project. By 1916, water levels had risen nine feet in the bay, the result of having turned what was once a tidal inlet into a freshwater connection to Lake Union (with a correlating drop in the water level of Lake Washington). Not counting the economic impact to shoreline businesses, the total cost of building the locks and the eight-mile-long ship canal was nearly $4 million. Over 227,000 cubic yards of concrete was used to construct both the locks and the dam.

Initial tests done by the Army Corps of Engineers in early 1916 allowed some ships to transit through the new locks. The May B II was the first passenger craft to go through, on February 5, 1916. One three-mast schooner, the Abner Coburn, weighing 1,972 tons, was a commercial vessel that successfully made it through with the help of the tug Wanderer. Another smaller ship, the US Coast Guard launch Orcas, went through on July 25, 1916. The small lock was opened on July 30, 1916, and the second, larger lock opened on August 3, 1916.

The following year, preparations were underway for an official dedication of the Ballard Locks on July 4, 1917. The steamship Roosevelt was tasked to lead a parade of boats through the ship canal from the locks, carrying the famous American polar explorer, Admiral Robert E. Peary. Captain H. Baird served as the “Fleet Commander” for the celebratory flotilla, which had a particular pecking order for vessels behind the Roosevelt. First would come the City or public vessels; next, those operated by the Seattle Yacht Club, then the Lake Washington Power Boat Association; the Duwamish Launch Club; the Queen City Launch Club; and finally, working boats of the fishing fleet.

The Roosevelt entered the locks from Shilshole Bay at 1:30 in the afternoon, with the passage through taking a full hour to complete. Citizens of Ballard led by the Booster’s Club band lined the shoreline to watch the ships pass through. The dedication event lasted all day and into the night, with speeches in Fremont at the Fremont Boathouse, followed by cruises on Lake Union to Lake Washington, and an evening party hosted by the North Side Commercial Club.

The namesake of the locks, Chittenden, was a Brigadier General with the Army’s Corps of Engineers. In 1905, he was assigned as the supervisor for the federal engineer’s office in Seattle. Newspaper accounts published the month of the Locks dedication describe his role as having “greatly hastened the work on the canal project by his warm personal interest.” That said, Chittenden is credited for having overseen the dredging work from Shilshole Bay to the Ballard wharves in 1906, as a key step towards the future creation of a ship canal and locks system.

David B. Williams, a local historian and co-author of the 2017 book Waterway: The Story of Seattle’s Locks and Ship Canal, has commented on the fact that some specifics about the Locks’ history just were not found: “[there was] information which we would have liked to include, such as who the workers were who worked on the locks; what was the origin of the apparently false quote from George McClellan about a canal creating ‘the finest naval resort in the world,’; when exactly did Harvey Pike actually start to try and dig his canal; and what work did Wa Chong’s crews do on the digging of the original canal between Lake Union and Lake Washington.”

Another interesting aside about the labor history of the locks is a personal observation: I’ve never come across any personal stories or family member accounts in the National Nordic Museum’s archives that speak about jobs involving the canal. There is a lot of information about shipyards and shingle mills that had to deal with rising water levels as part of doing business—but no tales specifically about workers.

The questions raised by researchers about labor for the locks project leave the door open to future discoveries about the Ballard Locks and their history. In the meantime, the locks continue to be an attraction and a gateway for commercial vessels and pleasure boats, and mariners young and old.